-

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

- admin on Cottbus Bird Census

- Flora Alexander on Cottbus Bird Census

- Flora Alexander on Proper Winter

- admin on Proper Winter

- Flora Alexander on Proper Winter

Archives

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- April 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- July 2018

- May 2018

- January 2018

- October 2017

- September 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- August 2013

- January 2013

- August 2012

- July 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

Categories

- Advent

- Antarctica

- Arabic

- Architecture

- Argentina

- Art

- Astronomy

- Austria

- Books

- Bureaucracy

- Computers

- Cottbus

- Czechia

- England

- Falkland Islands

- Food

- Germany

- Greece

- Home

- Hungary

- Ibra

- Indonesia

- Kitsch

- Language

- Learning

- Muscat

- Music

- Nature

- Netherlands

- Oran

- Oxford

- Pets

- Scotland

- Slovakia

- Society

- South Africa

- South Georgia

- Tamanrasset

- Travel

- Turkey

- Uncategorized

- Vietnam

- War

Meta

Oran 4/30: Camus’s flat*

Posted in Architecture, Books, Oran

Comments Off on Oran 4/30: Camus’s flat*

Reading List 7

A total of 60 for the first six months of the year (helped by having very little gainful employment for most of the time).

Literature

Oranges are not the Only Fruit — Jeanette Winterson

The Passion — Jeanette Winterson

To Kill a Mockingbird — Harper Lee

Travels with my Aunt — Graham Greene

The Corn King and the Spring Queen — Naomi Mitchison

Earthly Powers — Anthony Burgess

Athena — John Banville

The Noise of Time — Julian Barnes

Leo Perutz — Little Apple

Ulverton — Adam Thorpe

The Stone Raft — José Saramago

Sea of Ink — Richard Weihe

Galápagos — Kurt Vonnegut

All Quiet on the Western Front — Erich Maria Remarque

The Man-eater of Malgudi — R. K. Narayan

Sunflower — Gyula Krúdy

Campo Santo — W. G. Sebald

The Bottle Factory Outing — Beryl Bainbridge

Harriet Said … — Beryl Bainbridge

A Quiet Life — Beryl Bainbridge

The Dance of Death — W. H. Auden

The Restraint of Beasts — Magnus Mills

Heaven Forbid — Christopher Hope

The Arabian Nights — trans. Husain Haddawy

Radio Romance — Garrison Keillor

Eight Months on Ghazzah Street — Hilary Mantel

The Plague-Spreader’s Tale — Gesualdo Bufalino

The Tenement — Iain Crighton Smith

Several continuing themes here — the Wintersonathon continues from last year (though I’ve ground to a halt in Gut Symmetries), and the Bainbridgeathon begins. I read A Quiet Life at the same time as the Alan Bennett book below, and they merged into each other in a disturbing/enjoyable way.

More paper books of the early 90s: Ulverton was very different from what I had expected, the interconnected stories reminiscent of a deeper, if less funny, David Mitchell. Heaven Forbid managed to give a believable child’s-eye view with beautiful — and funny — use of language. In The Restraint of Beasts the humour was more Kafkaesque.

All Quiet on the Western Front was a book that I always thought I more or less knew without actually having to read it. Turns out I was wrong.

Trashy

Captain Corelli’s Mandolin — Louis de Bernières

The Black Book — Ian Rankin

Dead Beat — Val McDermid

SF/F

The Bloodline Feud — Charles Stross

Mixed Magics — Diana Wynne Jones

The Inverted World — Christopher Priest

Diamond Dogs, Turquoise Days — Alastair Reynolds

Binti — Nnedi Okorafor

Ninefox Gambit — Yoon Ha Lee

The Last Days of New Paris — China Miéville

Consider Phlebas — Iain M. Banks

The Wild Shore — Kim Stanley Robinson

More series — DWJ and Reynolds’ Revelation Space continue, and I’ve started the Culture series again from the beginning. Christopher Priest and Yoon Ha Lee were both new discoveries for me. The former turns out to be one of the grand old men of British SF, while the latter’s book is the first in a series of tough, but rewarding military SF by a queer Korean Texan. A first.

Non-fiction

The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot — Robert Macfarlane

Holloway — Dan Richards et al.

Civilization and its Discontents — Sigmund Freud

Introducing Heidegger — Jeff Collins and Howard Selina

Val McDermid — Forensics

The World According to Bob — James Bowen

Black Box Thinking — Matthew Syed

Demystifying Tibet — Lee Feigon

Fire Under the Snow — Palden Gyatso

Quiet — Susan Cain

Hiroshima — Robert Hersey

The Great Learning and Doctrine of the Mean — trans. He Zuokang

A Life Like Other People’s — Alan Bennett

Algeria, 1830-2000: a Short History — Benjamin Stora

Fire Under the Snow stood out here for the way it brought the occupation of Tibet to life. The cheerful anger of the author is something to behold. Hiroshima brought home another disaster, although I thought the emphasis on Christian missionaries and converts unfortunate (giving the impression that “the ones like us” matter more). The Old Ways was uneven, but it put me on the track of some other writers, and inspired me to start a series of Edward Thomas books at Distributed Proofreaders.

Gutenberg

The New English Canaan — Thomas Morton

John Holdsworth Chief Mate — W Clark Russell

Pictographs of the North American Indians. A preliminary paper. — Garrick Mallery

How to Teach a Foreign Language — Otto Jespersen

Animal Behaviour — C. Lloyd Morgan

In the Far East — William Henry Davenport Adams

And plans for the rest of the year: finish 100 books for the year (or maybe 104, for two per week); start on All of Shakespeare; and maybe Some of Austen, to be fair-minded; more by Arab/Algerian writers, or at least about about the region.

Gutenberging 2017

This year I finally managed to complete and post two long-term projects. The first was Pictographs of the North American Indians — A preliminary paper by the American Bureau of Ethnology, which started on Distributed Proofreaders back in 2004. It’s a substantial work, surveying the petroglyphs, tattoos and other drawings of the native Americans. A few of its highlights are:

a calendar painted on buffalo skin, in which each pictures represents a notable event from that year, so allowing accurate reference to dates:

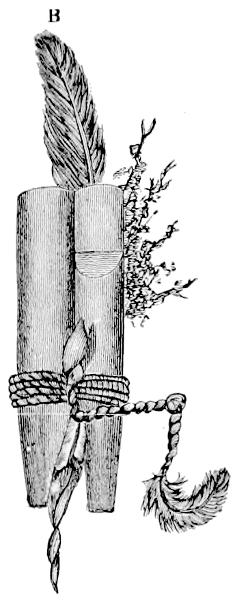

a diplomatic packet sent to the US president as a token of friendship, including a peace pipe and maize:

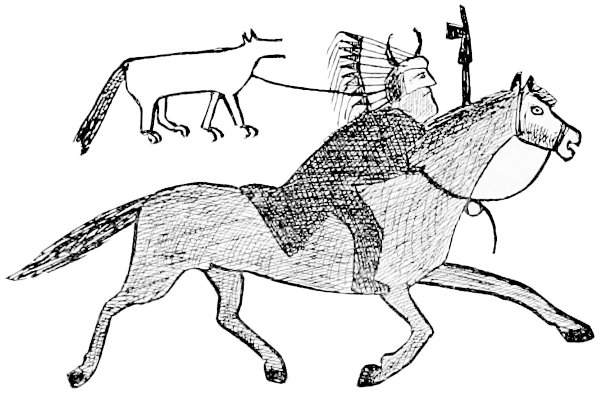

identification of particular Indians via representation of their names. Here, for example, the man is associated with a depiction of his name “Lean Wolf” — “lean”, because the wolf is incomplete:

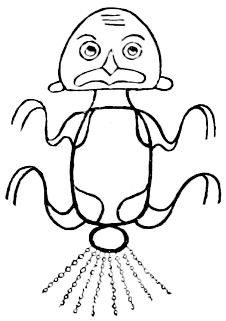

the wonderfully expressive Haida art, such as this squid:

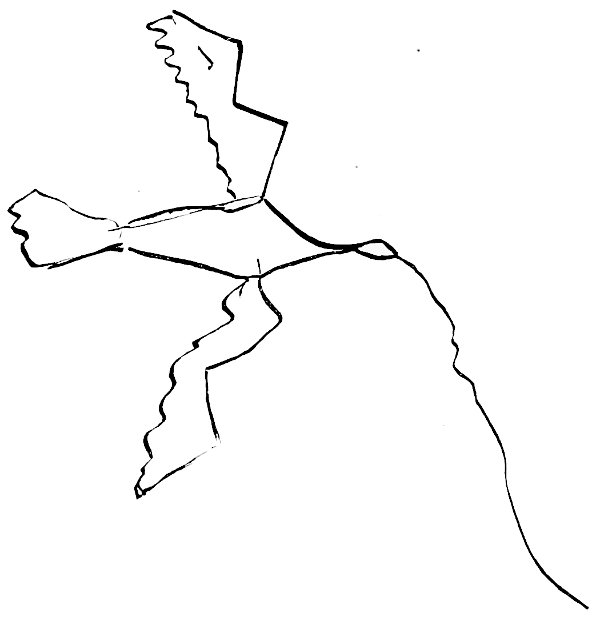

and the mighty thunderbird, with wavy line representing its magical voice:

That was of course only the preliminary paper, so the second project was the complete Picture-Writing of the American Indians, also thirteen years in the making, and taking over 800 pages to cover the same material in more detail, along with comparisons to folk art from across the globe.

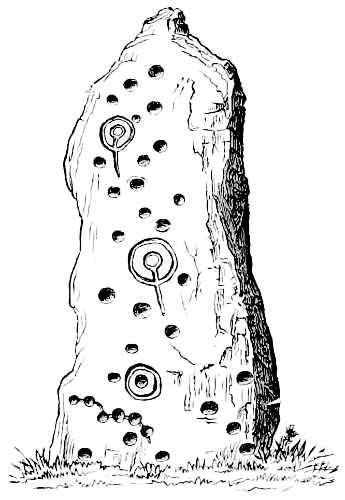

Here we have, for example, cup art from Scotland:

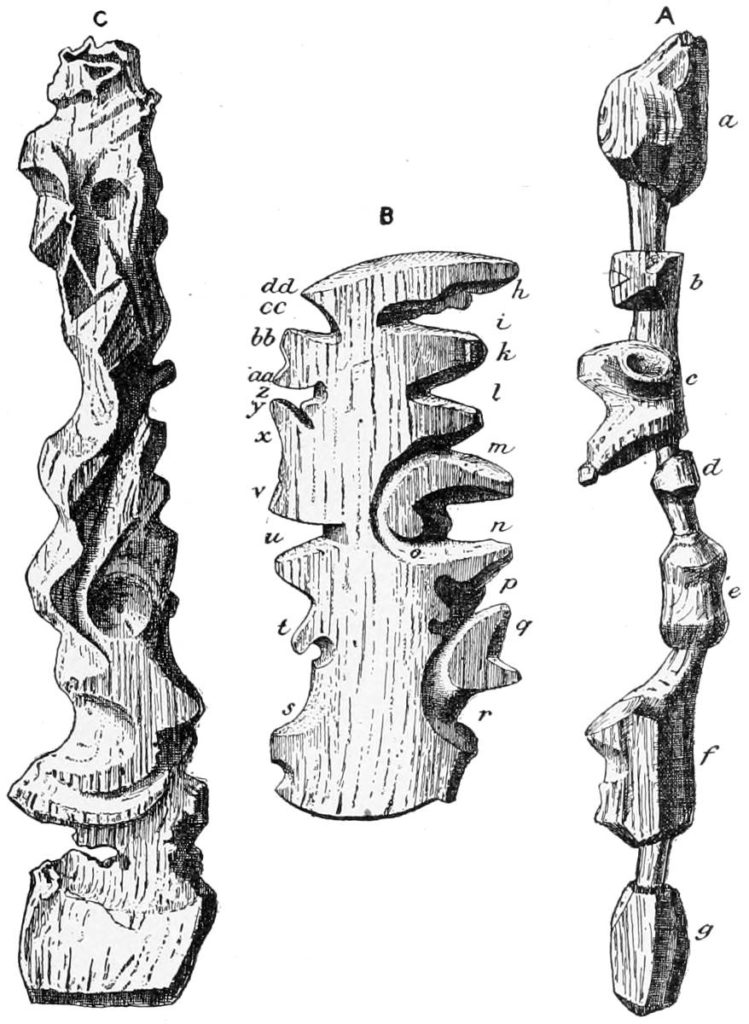

the Giant Bird Kalloo (“the most terrible of all creatures”):

and my favourite, a map of the coast of Greenland, in which the wood is carved to represent prominent coastal features:

After that I had some light relief with How to Teach a Foreign Language by the great Danish linguist, and pedagogical reformer, Otto Jespersen. His teaching philosophy is neatly summed up:

If something difficult is to be learned, the very first essential is to be much occupied with it; therefore the first condition for good instruction in foreign languages would seem to be to give the pupil as much as possible to do with and in the foreign language; he must be steeped in it, not only get a sprinkling of it now and then; he must be ducked down in it and get to feel as if he were in his own element, so that he may at last disport himself in it as an able swimmer. But what is most characteristic for the prevailing methods is that the translation with its accessories swallows up so much time, that there is none left for this free disporting in the foreign element.

There’s food for thought in a couple of quotations which he provides from Schuchardt:

one really cannot begin to learn the grammar of a language until one knows the language itself.

Obwohl ich mich seit geraumer zeit mit der theorie der sprachen beschäftige, hege ich noch heutzutage eine abneigung gegen die systematischen sprachlehren.

And an unsettling one to finish with:

Gesprächige leute von engem gedankenkreise sind für den anfang die besten lehrmeister

The OC

Yesterday saw a rather special musical event in Oxford: the 17th performance (since it was written in 1930) of the Opus clavicembalisticum (hereafter OC) by Sorabji. Supplier of stamina and skill on this occasion was Jonathan Powell.

Sorabji was a very eccentric English/Parsi composer, roughly in the style of a mix of Busoni, Liszt and Scriabin. He was born a slightly less exotic “Leon Dudley Sorabji”, but changed his name to emphasise his Parsi identity. After an attempted performance of part of the OC in 1936, he banned further public performances of his work until the 1970s.

The OC is in twelve movements (some up to an hour in length), which start huge and increase from there. Among them are four fugal movements, containing in turn one, two, three and four separate fugues. Light relief is provided by a couple of sets of themes and variations, with 49 and 81 variations respectively. The dedication is a good example of the composer’s sense of humour and writing style:

TO MY TWO FRIENDS (E DUOBUS UNUM) HUGH M’DIARMID AND C.M. GRIEVE LIKEWISE TO THE EVERLASTING GLORY OF THOSE FEW MEN BLESSED AND SANCTIFIED IN THE CURSES AND EXECRATIONS OF THOSE MANY WHOSE PRAISE IS ETERNAL DAMNATION.

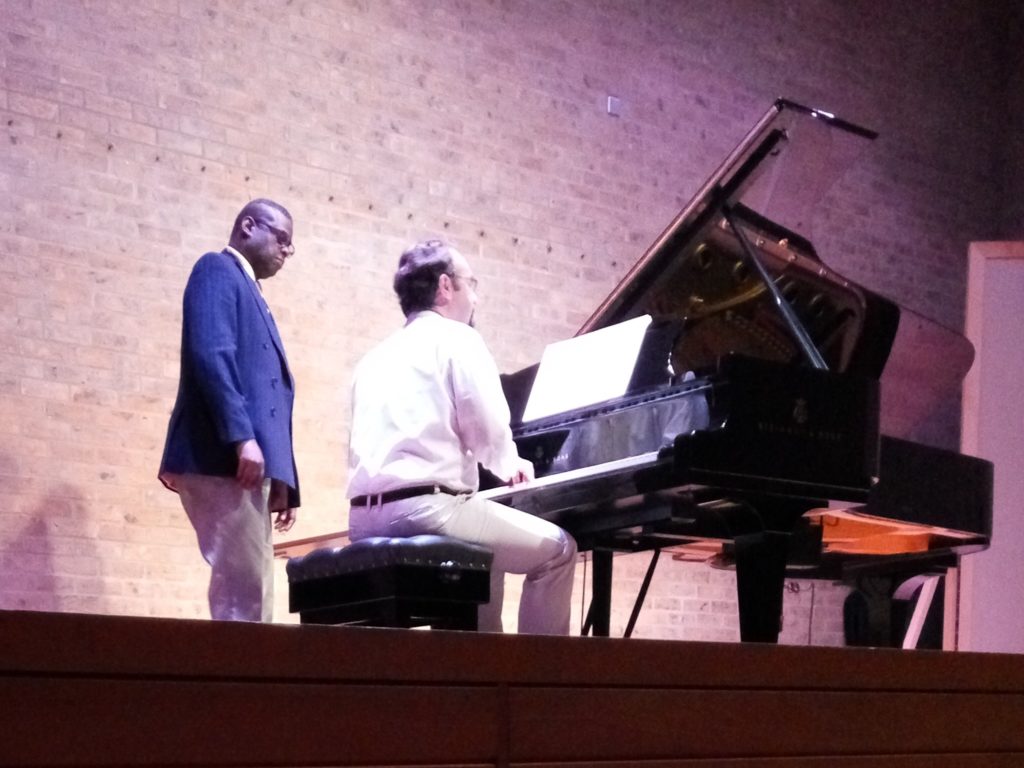

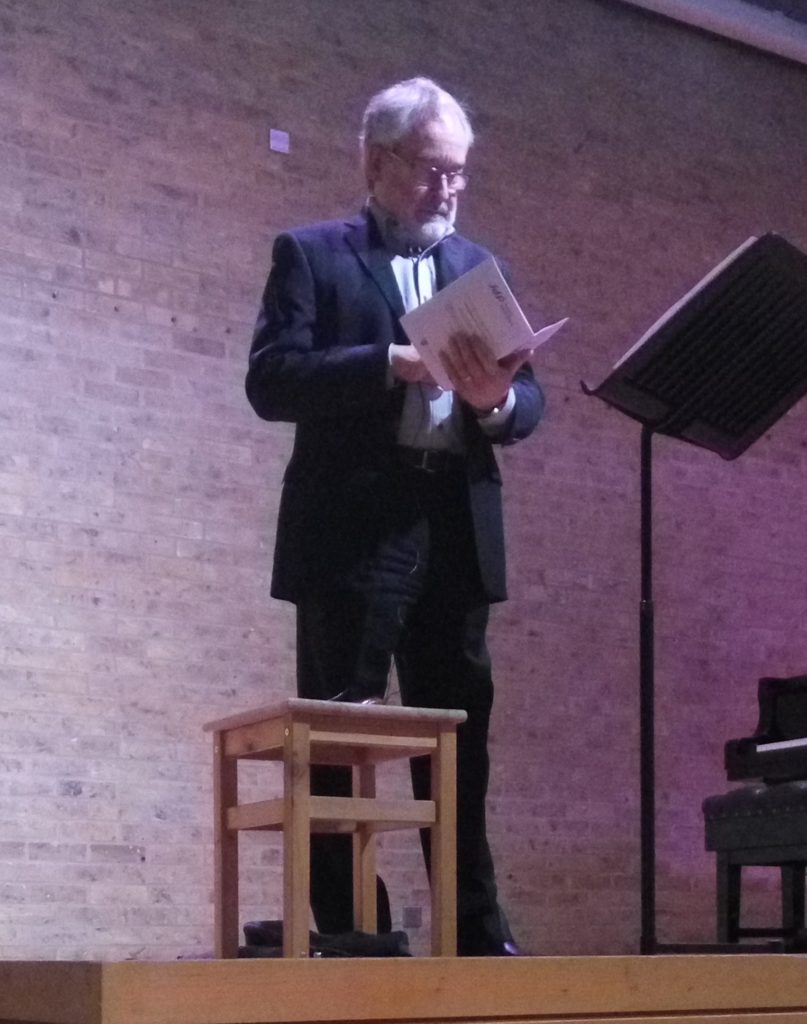

The concert was billed as four hours, plus intervals, so it started at 3.30. Quite a few of us also went to the pre-concert talk which started an hour earlier, given by Alistair Hinton–composer, friend of the composer, and founder of the Sorabji Archive. Possibly occasional Alasdair Gray impersonator.

The concert actually ended at 9pm, so with two 20 minute intervals, that was still almost five hours of music.

What kind of of audience turns up for such an event? Frankly, not much of one. I estimate we started with about 60, ⅔ of whom made it to the end. Fortunately this didn’t include the woman who brought her two young children, in the mistaken impression that five hours of modernist fugues would calm them down (they ejected themselves some time during the second movement); or the man who wandered out during one movement, and in again during the next. Or the chap at the back who had set his watch to beep every hour. At some points the poor herculean Mr Powell was driven to tut and shake his head whilst wrestling with his counterpoint. The survivors at 9 o’clock were almost all men of a certain age, a few of whom had brought along their own scores to follow along.

For those of us who did last to the end, it was quite an experience. While I can’t claim to have taken in every twist and turn, there was always something to enjoy, and Mr Powell kept the attention throughout. Once in a lifetime, this was a great way to spend a day.

Posted in Music, Oxford, Uncategorized

1 Comment

Otmoor Days

A healthy walk from Headington is the Otmoor reserve, which the RSPB has been rehabilitating over the last twenty years.

The reserve is dominated by a series of ponds and lagoons, so waterbirds are a big feature.

Lapwings have been displaying:

Only one of these redshanks was in the mood, though:

Coots are more advanced, though their chicks still look like dinosaurs:

One of the lagoons is equipped with an island and artificial nesting sites for some lucky common terns:

In the reedbeds and hedgerows adjoining the water, there are plenty of warblers:

Up above there are swarms of hobbies, which catch dragonflies in their claws and eat them on the wing:

I’m not sure if the buzzards were making love or war:

Otmoor has one of the 350-odd breeding pairs of marsh harriers:

And of course, it wouldn’t be Oxfordshire without these beady eyes:

Watch out!

Little Guys

In between raptor and heron appreciation, we’ve been taking some time recently to enjoy the smaller dinosaurs. The main disadvantage is of course that they’re harder to spot and (especially) to photograph, so picture quality decreases with size. In reverse order, then:

Starling

75g. He mainly qualifies for this list on the grounds of unjust neglect rather than physical dimensions. How unjust that neglect is:

Sparrow

30g. Little symphonies in brown, with an unexpected ability to hover:

Blue Tit

11g.

Wren

10g. This one has built a very snug nest under a conveniently placed old fertiliser sack, which we’ll need to stake out over the next few weeks.

Goldcrest

6g. (Or possibly a firecrest, but with a definite crest!)