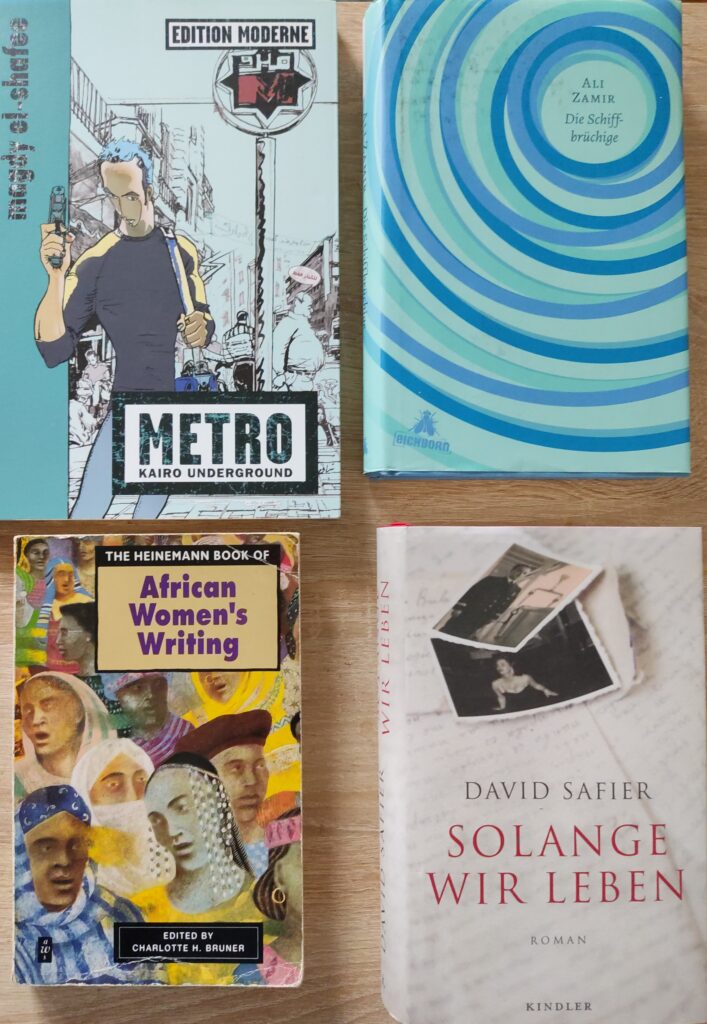

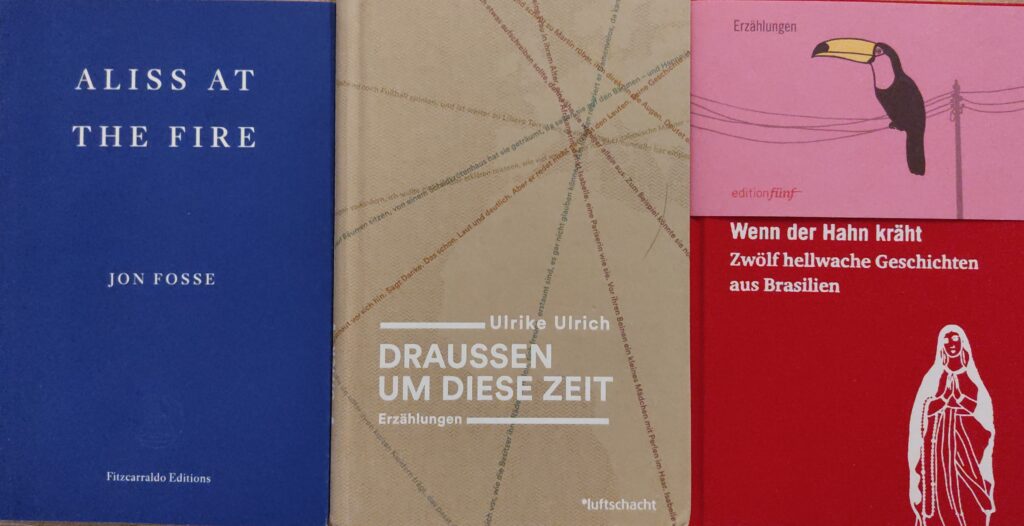

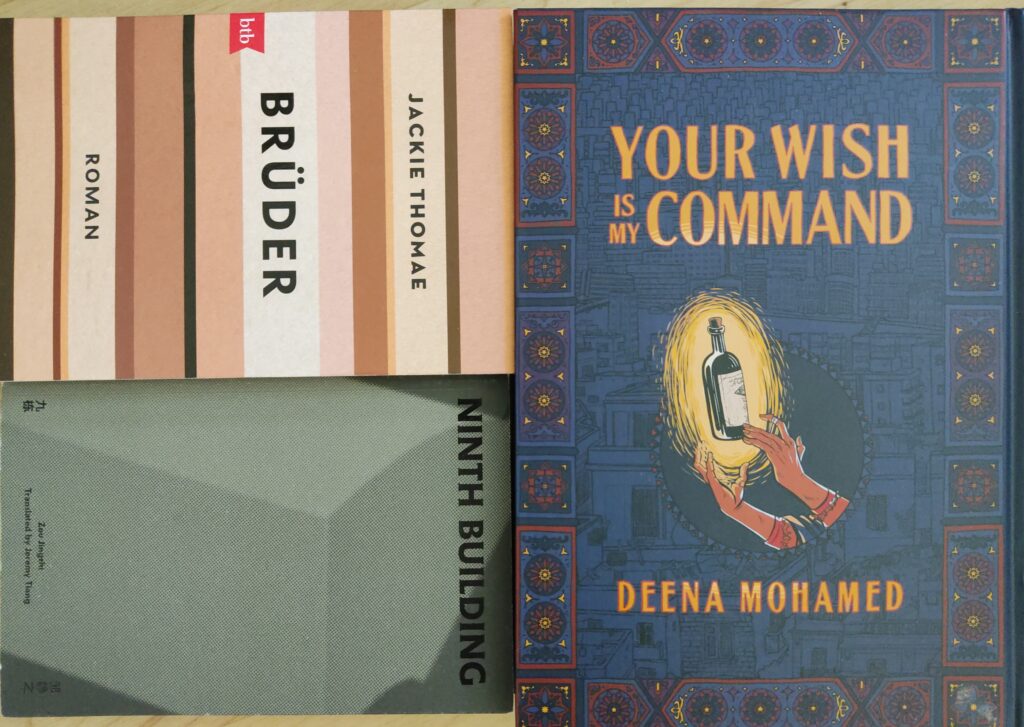

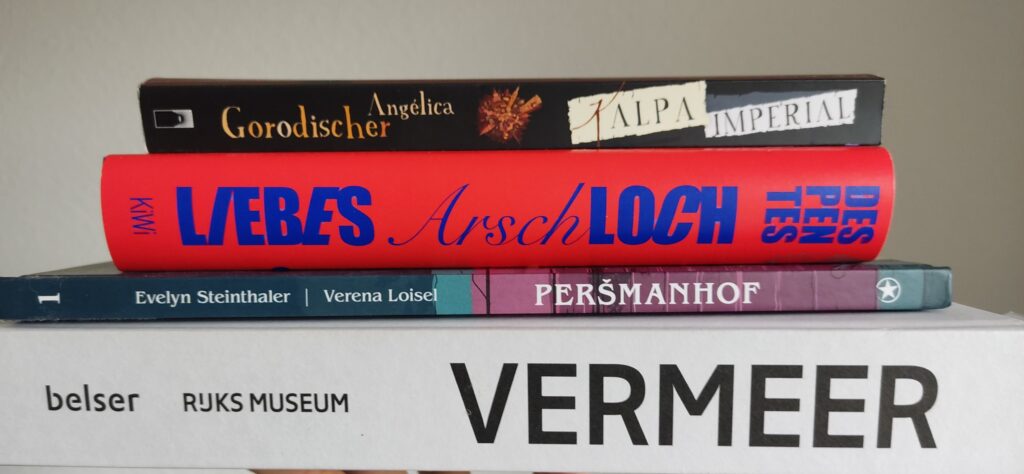

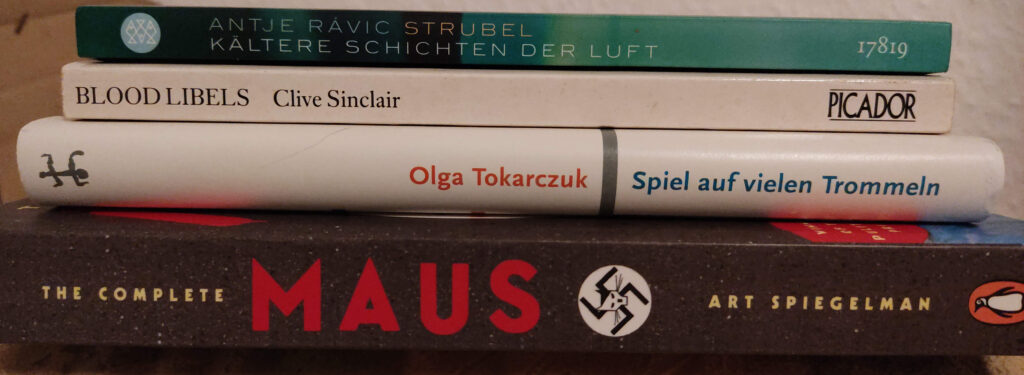

I finished a modest seven books this month, mainly because it was a Proust month (and Oxen of the Sun in Ulysses took a while). All except Marcel were women for Women in Translation month (two actually in translation, and four in the original German).

- The Stories of Eva Luna — Isabel Allende tr. Margaret Sayers Peden

- Liebe ist gewaltig — Claudia Schumacher

- All the Lovers in the Night — Mieko Kawakami tr. Sam Bett and David Boyd

- Sibir — Sabrina Janesch

- Sodom and Gomorrah — Marcel Proust, tr. John Sturrock

- Madgermanes — Birgit Weyhe

- May Ayim: Radikale Dichterin, sanfte Rebellin — Ika Hügel-Marshall et al.

Starting with the odd one out, Sodom and Gomorrah is where we find out, amusingly, that everyone except Marcel is gay. Marcel, meanwhile, sleeps his way through fourteen of Balbec’s little band of girls, as you do. Other highlights on my mastodon thread: https://mastodon.green/@slnieckar/110980369394661379

The Stories of Eva Luna were my short stories for the month (plus Lispector, which I’ll hopefully finish in September for my South American month). Interestingly the stock characters which in e.g. Garcia Marquez look like dodgy sexual politics — the macho general, the happy whore, the silent well-brought-up girl — are the same ones she uses. Lispector’s stories, in comparison, are full of neurotically complex characters; I know that she’s considered a very “European” writer, but the question of how much is due to the writer’s approach, and how much to the subjects (the period?) will require more reading.

Liebe ist gewaltig is a brilliantly written story of the narrator coming to terms with childhood in a violent family, where the father’s rages warp his wife’s and children’s characters. Schumacher adjusts the narrative voice to show the movement (not always progress) from smartarse teen to alienated adult (with a terrifying shift from first to third person as the protagonist becomes a Stepford wife).

All the Lovers in the Night reminded me a lot of Breasts and Eggs, both heavily featuring alcoholic women in publishing having inarticulate conversations. This time, the protagonist is an enigmatic (autism spectrum?) proofreader, who tries to find a way through life through her interactions with the other characters. Despite her difficulties connecting with them, the tender portrayal has a powerful effect on the reader.

Despite the name, Sibir actually takes place in Kazakhstan (and in Germany after the characters’ migrations westward). The ex-Soviet Germans are a substantial, but as far as I can tell little talked-about group in this country, so it was a fascinating read. The plot is occasionally creaky, but the focus on children’s worlds in each narrative thread was very effective.

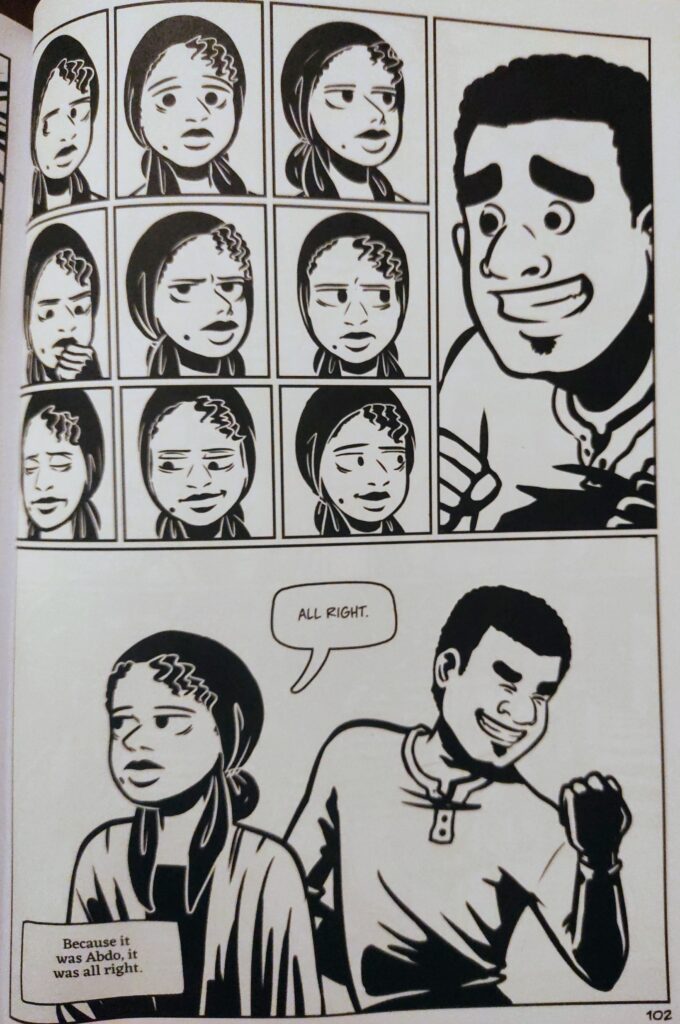

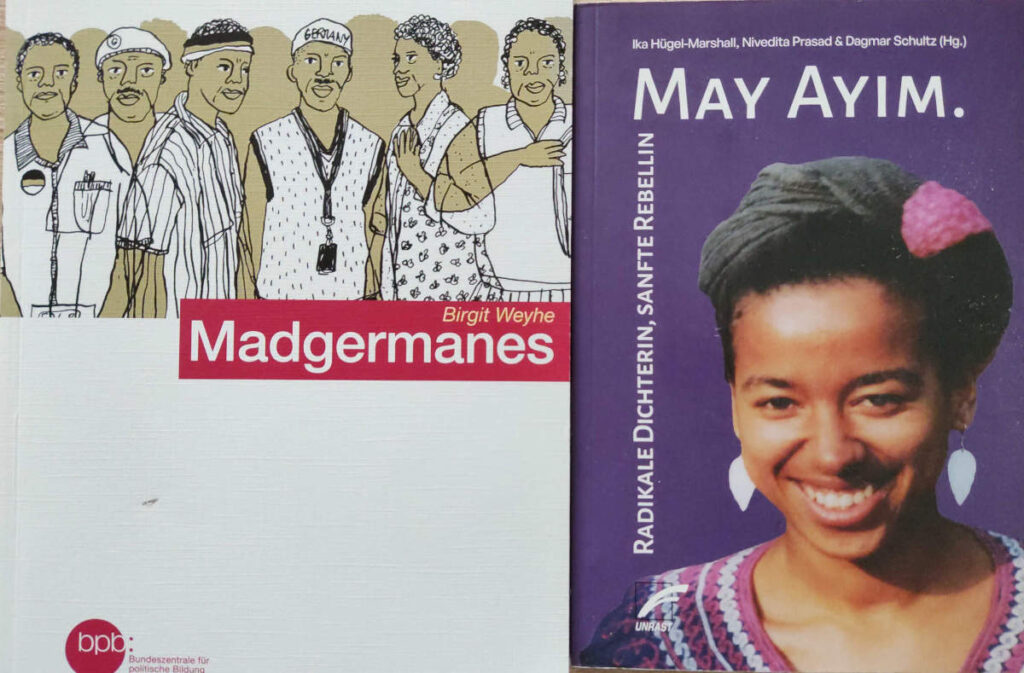

Graphic novel for the month was Madgermanes (explained in the novel as deriving from “made in Germany”). It tells the story of three Mozambicans who worked in the DDR, with each in turn presenting their own perspective and deepening the reader’s understanding. Both in Germany and (for those who return) in Mozambique, they face exploitation and hostility, though the positives are also portrayed. The visual style creatively combines traditional comic and African motifs.

Lastly, May Ayim: Radikale Dichterin, sanfte Rebellin shows another side of Black life in Germany. There is a mixture of recollections of Ayim by her friends and family, unpublished (very dark, late) poems, and some powerful, mostly academic writing of Ayim’s, which together show the prejudice she and other Afro-Deutsch people faced, and her marvellously good-natured ability to deal with it and process it in her work and activism.

As I mentioned, next month is South American month. I might not get through very many, because one of my selected books is the voluminous 2666, but there are a few I’m eyeing up….