I finished a healthy eleven books in a short month, mainly due to several volumes of short stories; four books in German, and seven of the eleven by women/POC. My main focus this month was reading some of the original “Best of Young British Novelists” from 1983, especially one I hadn’t read previously. No longer young, of course, but it was great to read some new old writers. For German I had a very loose plan of “winners or nominees from the Deutscher Buchpreis”.

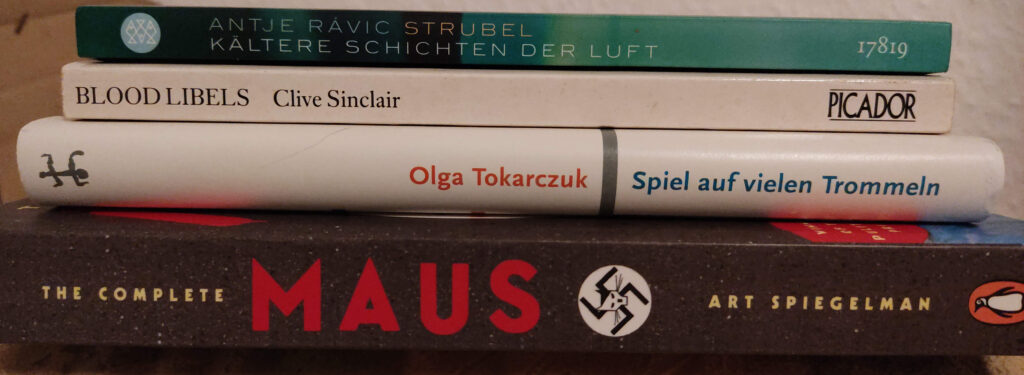

- Blood Libels — Clive Sinclair

- Episodes — Christopher Priest

- Banthology — Sarah Cleave et al.

- Das glückliche Geheimnis — Arno Geiger

- Mozambique Mysteries — Lisa St Aubin de Terán

- Die Katze und der General — Nino Haratischwili

- Spiel auf vielen Trommeln: Erzählungen — Olga Tokarczuk tr. Esther Kinsky

- Piranha to Scurfy and Other Stories — Ruth Rendell

- The Complete Maus — Art Spiegelman

- Noonday — Pat Barker

- Kältere Schichten der Luft — Antje Rávik Strubel

Starting with the BYBNs, Christopher Priest was the only one I’d already read. Some of the stories themselves were familiar from another of his collections, but there was an interesting mix of styles from the length of his career. A highlight for me was Palely Loitering, where a meeting between past and future versions of the narrator are used to show their different perceptions, each convinced that he is right:

I could remember how I had seen myself, my older self, that is. I recalled my ‘friend’ from this day as callow and immature, and mannered with a loftiness that did not suit his years. That I (as child) had seen myself (as young man) in this light was condemnation of my then lack of percipience.

Blood Libels was one of the most unpleasant books I’ve ever read — something of a speciality of the time, perhaps, with Ian McEwan and Iain Banks also both in their shocking phases. In this case it seems to be combined with my idea of Philip Roth’s style (another omission of mine until now), so the sexual violence at least had an interesting Jewish flavour.

Noonday turns out to be the last part of a trilogy, but it stands up well enough on its own. It’s fantastically written, adding a direct, modern feeling to the period (Second World War) atmosphere:

Two glasses of whisky later, Rachel was already slightly slewed. She squinted at Elinor, as if a sea-fret had suddenly blown into the drawing room.

They found the family still in the drawing room, slumped in armchairs with the dazed, disorientated look of the recently bereaved and the totally pissed.

Further along, by the yard door, a man’s head rested on the concrete, severed neatly at the neck, one eye closed. Kenny pushed it to one side with his foot and opened the door into the alley.

As Paul turned the corner, he saw a stick of bombs come tumbling down the beam of a searchlight on to a building fifty yards ahead, an extraordinary sight, like a worm’s-eye view of somebody shitting.

I found the plot thread about the obese medium (reminiscent of Hilary Mantel’s Beyond Black, I’m not sure how coincidentally) hard to take for the same reasons as in that case (essentially, it seems that she has real supernatural powers), but the book as a whole was very satisfying.

The biggest surprise was Lisa St Aubin de Terán: I’d always been vaguely aware of her existence, but no more; it turns out that she moved to northern Mozambique almost 20 years ago, and since then has been setting up and running a college of tourism and agriculture. Mozambique Mysteries is not particularly mysterious, and in terms of writing style it’s quite straightforward, so perhaps it wasn’t the best place to start, but it was fascinating to compare her experiences with my own at the other end of the country. There are some disconcerting oddities: she talks about her determination to establish schools in Africa from before she had ever visited, and devises her own herbal remedy against malaria, but generally she shows an awareness that her position in the community is accidental: “Being a writer doesn’t bring much credit in an area where there are no books to speak of.”

these same so-called ‘backward’ villages have a form of democracy that works, that truly represents its people, that gives the chance of equality to all members of the community, and pre-empted the notion of a welfare state by several centuries.

Her right-hand man at the college has the best line in the book, sideswiping whitey while praising their drinking ability:

I always thought that colour was just about your skin and a certain hardness of heart, a lack of compassion, but now I am wondering if it isn’t a lot more than that. Six bottles in just over an hour!

Occasional references to her earlier life show the uniqueness and universality of her experience:

My expectation of how life should be was so rarefied that I managed to squeeze a few lives into the 1970s without really noticing them pass by. During that decade, I was benignly stalked by, and cradle-snatched by, a Venezuelan revolutionary and taken to his inherited lands in the Andes, and I became a farmer and a mother, a writer and then a refugee without realizing that that was my life, rather than the other more elusive dreams I was endlessly chasing.

Graphic novel of the month was The Complete Maus, by Art Spiegelman, and it’s brilliant. The representation of the characters by different animals is very effective, creating enough distance without trivialising the events, and the juxtaposition of the Holocaust narrative with the long-term effects on Spiegelman’s father is extremely moving.

Two English story collections: Banthology contains stories by writers from the countries affected by the Muslim travel ban of the early Trump presidency, while Piranha to Scurfy presents tales of the (mostly) uncanny by Ruth Rendell. Both were mixed bags, as so often, but the two novellas in the Rendell collection were impressively atmospheric.

Spiel auf vielen Trommeln also tends towards the weird, if with more absurdist humour. I particularly liked the opening story, about a writer’s struggles with his doppelgänger. Kältere Schichten der Luft is a fascinating precursor of Strubel’s recent Blaue Frau — a mysterious woman appears (by water!) in a Nordic country, and there’s a tale involving sexual violence, queerness, and memory. In this case there’s less definite resolution than in the later work, so it’s less immediately satisfying, but the atmospheric Swedish summer setting is attractive, and there’s plenty to think about.

Das glückliche Geheimnis was the first of my birthday subscription books, and an excellent start! At first I assumed that it was fictional rather than a memoir; once I realised around half-way through, it was interesting how my mental picture of the situation changed — less cartoon-like, and more realistic in my preconceptions of what could and couldn’t happen in the book.

Finally, Die Katze und der General was certainly long (23 hours in the audiobook); I’m not sure it really had to be, but it was enjoyable to follow Haratischwili wherever she decided to take the story. The performances by several different narrators were excellent. I liked it enough that I’m planning to crack on with Das achte Leben when I have about 40 hours spare.

Next month, a world tour of German, plus volume two of Proust….