Just eight books finished this month (but some whoppers): four by women/POC, (just) three in German, one in Portuguese, and just three that were part of my original plan. For the six months, 50 total, 35 by women/POC, 26 in German.

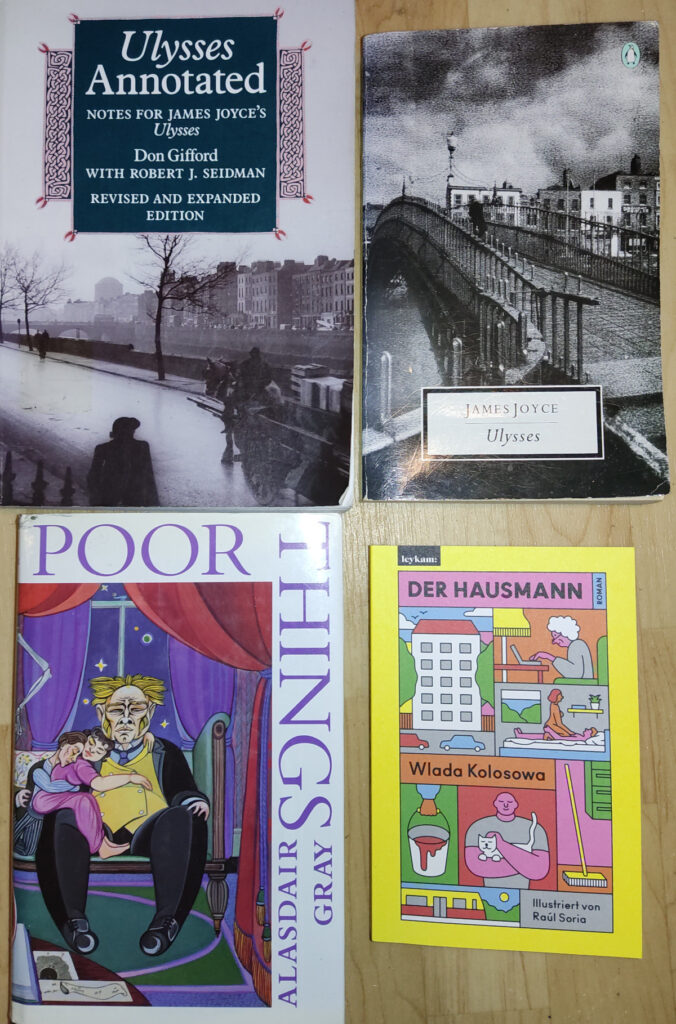

- Poor Things — Alasdair Gray

- Katz und Maus — Günter Grass

- Luft und Liebe — Anne Weber

- Memórias de Uma Envelhescente — Judith Nogueira

- Der Hausmann — Wlada Kolosowa

- The Mirror and the Light — Hilary Mantel

- Finding Time Again — Marcel Proust, tr. Ian Patterson

- Ulysses — James Joyce

The plan was to read recently-departed writers: interpreting “recently” quite flexibly for Alasdair Gray and Günter Grass. Hilary Mantel was the only other one I managed to complete, and the almost 40 hours that one took left Martin Amis and A. S. Byatt to be completed (and Milan Kundera to be started) another month.

Poor Things was also a re-read, and that’s yet another thing I want to start doing more (ideally one each month, along with my four German, one Portuguese, one graphic novel…). There was a lot I’d forgotten, probably a lot I appreciated more this time round, and lots of great Gray writing:

“It is hard not to pity those whose powers separate them from all the rest of us, unless (of course) they are rulers doing the usual sort of damage”.

Katz und Maus is the second part of the Danzig Trilogy, but for some reason I’d left it until last. It was very enjoyable to go back to the world of the other two books (Oskar, Tulla Pokriefke etc. turn up again), making this almost a re-read itself, while the novella format created a very different storytelling experience (much more direct, though the diversions of the other two books have their own virtues).

Something similar happened with The Mirror and the Light: a trilogy read in the proper order this time, it was much easier to follow having already been introduced to the main characters. I enjoyed this volume more than the first two, perhaps for that reason, perhaps because Cromwell’s story reaching its conclusion creates more urgency in the story. That despite the vast length of the book — I never grew tired of his company, especially in Ben Miles’ excellent performance of the audiobook.

Luft und Liebe is another short book, in typical Anne Weber-style blending fairytale elements with life in contemporary France. The conceit of the narrator telling her story through her own characters is brilliantly executed, with the distancing effect (indirectness, this time!) heightening the emotional impact.

Der Hausmann was my graphic novel for the month — sort of. This is another formally extravagant book, combining various texts produced by the characters (a graphic novel, a blog, instant messages) alongside the narrative of the househusband of the title. The events are mostly comic, sometimes tragic, and always engaging.

Memórias de Uma Envelhescente is hard to categorise, but is basically a memoir of an “envelhescente” — a word which I think English lacks; roughly, “ageing person”. It was a bit of a shock to find that the writer felt the need to start the book when she started to become old — at the age of 39. The biography is taken as a basis for philosophical commentaries which never descend into self-help banalities.

Lastly, I finished two big reading projects: again, both re-reads. In Finding Time Again (translated by Jenny Diski’s Ian Patterson!), Marcel finds that he’s also become old, while a character “in her fifties” takes pleasure from watching her contemporaries dropping around her. Proust the writer died at 51, so he may have a point. More highlights in my mastodon thread: https://mastodon.green/@slnieckar/111665384530178899

Finally, Ulysses. Not much to say beyond the obvious — this is really a book which needs multiple re-readings, and doing it with Don Gifford’s notes brought me much closer to being able to say I understand (most of) it.

Next projects: as I mentioned, I have an ever-growing list of things I’d like to do each month, which are not all going to happen every time. One non-prose-fiction per month would also be good. Then I’m planning a few more country months (Spain, DDR); in the first half of 2024 I’d like to read one from each European country. And there are some group reads that I’d like to take part in: possibly Der Zauberberg, definitely Portuguese in Translation reads and Kate Briggs/Roland Barthes in #KateBriggs24….