I finished nine books in May, mostly as part of a POC-reading month: so seven books by POC, one other woman, and a token white male. Only three in German, but two of those were pretty chunky.

Ninth Building — Zou Jingzhi tr. Jeremy Tiang

Hadithi & The State of Black Speculative Fiction — Eugen Bacon and Milton Davis

Indigo — Clemens J. Setz

Your Wish is My Command — Deena Mohamed

Black Spartacus — Sudhir Hazareesingh

Two Thousand Million Man-power — Gertrude Trevelyan

Wo auch immer ihr seid — Khuê Pham

Old Land, New Tales — Chen Zhongshi and Jia Pingwa (ed.), multiple translators

Brüder — Jackie Thomae

Ninth Building was unfinished as part of my International Booker month in April, and fitted in well here too. It’s an excellent book: Zou presents vignettes of the Cultural Revolution years in two sections, drawing on his childhood and young adult years respectively. In both, the juxtaposition of revolutionary madness and everyday life both highlights the contrast, and makes the bleak circumstances a nevertheless enjoyable read. The final section, consisting of a short selection of poem, didn’t grab me in the same way, but that may be just me.

The other Chinese book this month, Old Land, New Tales, is a collection of stories from Shaanxi province. The slightly odd nature of the project presumably has some bureaucratic origin, as reflected in the unintentionally comic potted biographies of each author, which focus on their association memberships and positions; they address the works mainly via lists of titles (mostly dull, but some intriguing: “Mr. Sister, … Champion Sheep, … Martyr Granny”) and po-faced comments (“he has held up the ideal of equality and created numerous characters with high morals and a great sense of ethics”). A lot of the stories are in a similar vein (honest, sturdy peasants, steadfast party officials), and Xi’an, the capital and a great world city, is bafflingly absent. All of which sounds awful, but there are some gems towards the end of the book where the authors attempt much more interesting things.

The other collection of stories this month was Hadithi & The State of Black Speculative Fiction, another of Luna Press’s story/lit-crit hybrids. The stories are by two writers, of which I found Bacon’s focus on human experience the more engaging.

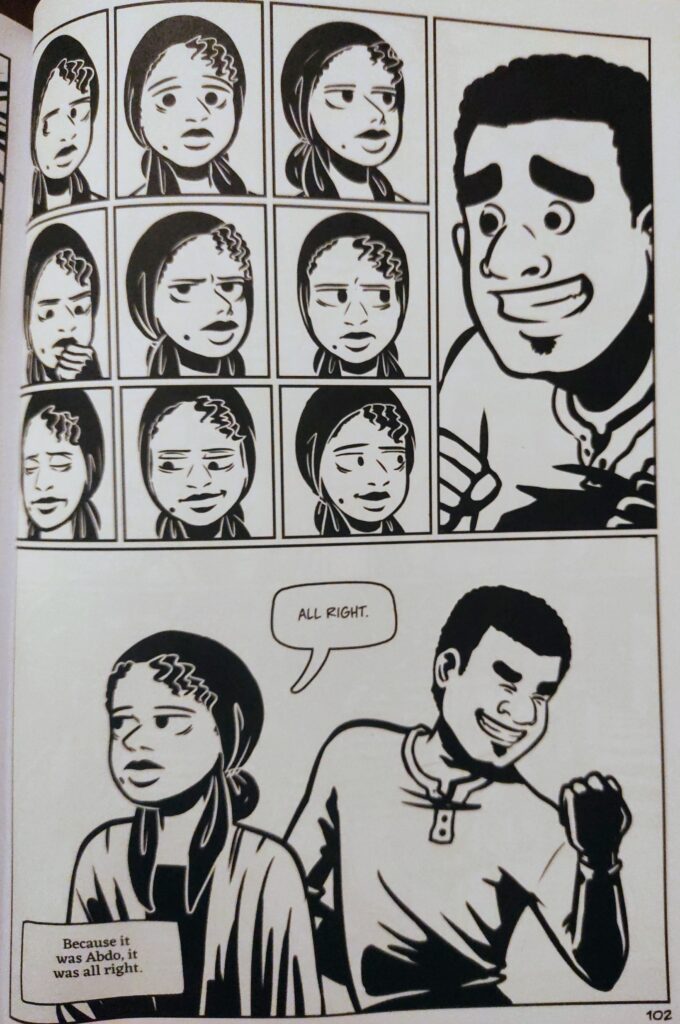

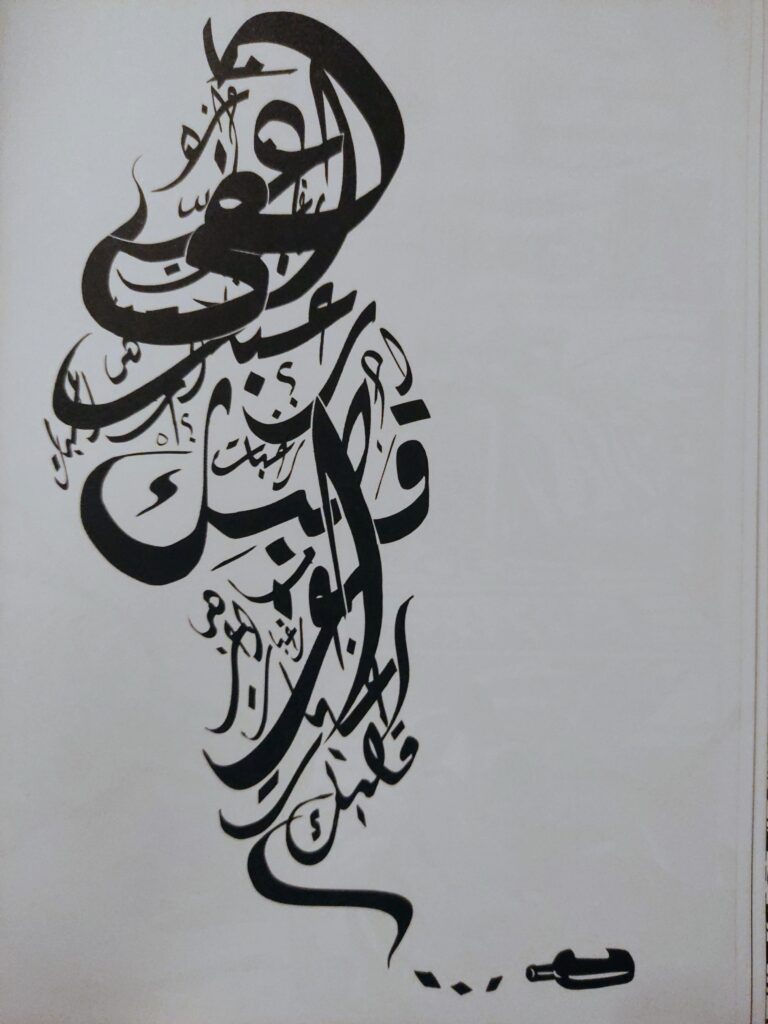

Turning to a thoroughly brilliant book, Your Wish is My Command is an Egyptian graphic novel, set in an alternative world where wishes really do come true. As in the classic stories, the wish allows Mohamed to explore the difference between what we want and what is good for us, with a great blend of thoughtfulness and humour. The art is also fantastic, especially the calligraphic genies:

Black Spartacus is a biography of the Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture; it presents a fascinating figure who combined great military and political abilities, religious and revolutionary ideals, and a sizeable ego. The author is very, perhaps overly sympathetic to his subject (his megalomaniac later years are not ignored, but arguably sugar-coated), but Louverture was clearly an extremely impressive man.

Two of the German books base their stories on the lives of those who came to Germany to study. In Wo auch immer ihr seid, the narrator’s parents came to the West and never left, becoming estranged from their family in Vietnam and later America through a series of misunderstandings. The movement of the plot is clunky at times, but the author is excellent at showing the touching and humorous side of diaspora Vietnamese life.

The second book, Jackie Thomae’s Brüder, has an unusual two-part structure, each telling the story of a son fathered by a Senegalese student in the East. The contrasting lives of the two are shown with great style and empathy, making the book a very satisfying whole.

Indigo is another great book by Clemens J. Setz, in his unique style. Ole Lagerpusch narrates the dialogue particularly well, drawing out the (realistic) absurdist humour. The novel (from 2012) has particular resonance now: a mysterious disease among children produces ill-effects when anyone approaches them, forcing the adoption of a social-distancing regimen. Two strands focus on one Indigo child, Robert, and his teacher: Clemens J. Setz.

Finally, I read Two Thousand Million Man-power for a book club discussion, and am pleased to have found another writer (very) roughly comparable to Dorothy Richardson. There’s a lot of overlap between the world of Pilgrimage and Trevelyan’s characters, from the seedy lodging houses to the political meetings and the ABC cafes. The gimmick in this novel is the presentation of the central relationship against the background of events across the globe: sometimes reminiscent of The Dead (“out in the country it was dark and quiet to the west”), sometimes personal, sometimes political (“Poland was making a defensive alliance with Rumania”). The effect, combined with the vicissitudes the characters go through, is very powerful, though not always an easy read, and the onward rush of modernity is again a very topical theme.

Next month, my anti-plan is to have as varied a selection of genres as possible….