I finished eight books this month, mostly as part of a South American reading month (inspired once again by the Portuguese in Translation book group, which this time did Crooked Plow). Only three in German, mainly because 2666 took up 40 hours of my listening time. I count five of the eight as by women/POC, but the latter group gets tricky to define in e.g. Brazil (I found a timely article on Machado de Assis here: https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/articles/cl7xvyz1eyro ).

- Crooked Plow — Itamar Vieira Junior, tr. Johnny Lorenz

- Budapest — Chico Buarque, tr. Karin von Schweder-Schreiner

- Geschwister des Wassers — Andréa del Fuego, tr. Marianne Gareis

- The Complete Stories — Clarice Lispector, tr. Katrina Dodson

- 2666 — Roberto Bolaño, tr. Natasha Wimmer

- Daytripper — Fábio Moon and Gabriel Bá

- Epitaph of a Small Winner — Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis, tr. William L. Grossman

- Sieben leere Häuser — Samanta Schweblin, tr. Marianne Gareis

Crooked Plow (and the accompanying discussion) was interesting in large part because of the culture in which it is steeped: rural peasants who are (largely — that troublesome classification again) the descendants of black slaves, and who continue to live lives which amount to something very like slavery. The Jaré religion plays a central part in their lives, and in the lives of the protagonists in particular; the connection between spirits, people and land is not just local colour, but central to the characters and their story.

Another Brazilian book, Geschwister des Wassers, is in some ways similar: a realist story of development through the construction of a hydroelectric dam collides with fantastic elements (characters disappearing into coffee filters, the dead transformed into ticks) which are accepted by some characters, but rejected by others. Del Fuego combines this with a laconic, fairy-tale style to make a highly enjoyable read.

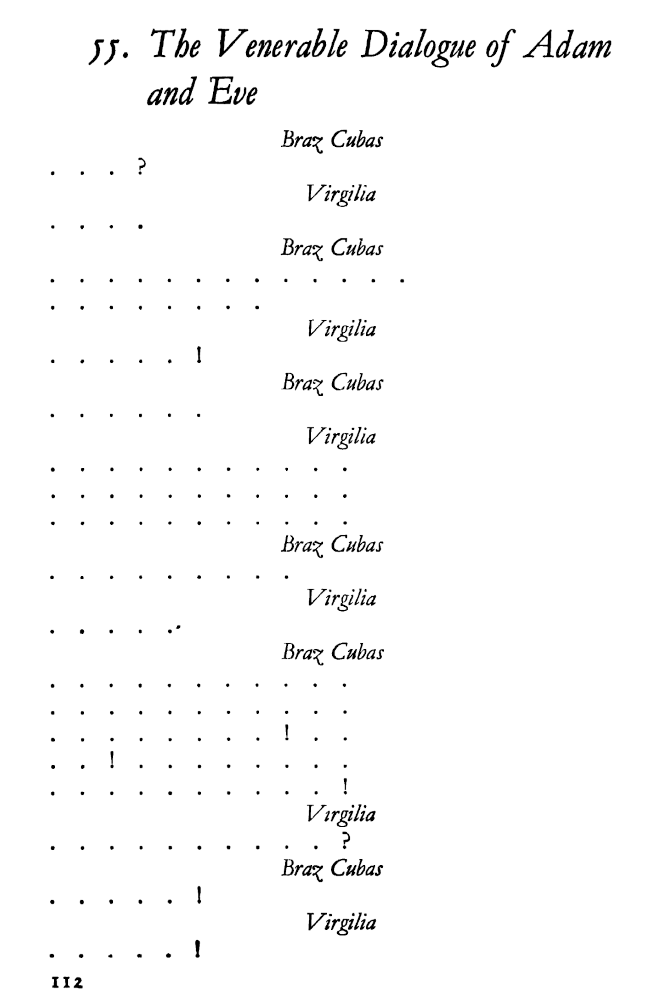

Epitaph of a Small Winner also blends whimsy and realism; for an example of the former, enjoy chapter 55:

Narrated by the protagonist after his death, this is a kind of Brazilian Tristam Shandy: ironic, metafictional, but with a strong satirical edge (witness the narrator’s excusal of his brother-in-law’s brutality as being required by his business being the smuggling, rather than the legal trading, of slaves). The original title is Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas (The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas), and this happened to be only the first book this month to concern a dead Brás.

The second was Daytripper, this month’s graphic novel. It tells the story of Brás de Oliva Domingos’s life, through a series of episodes at the end of each of which Brás dies. The relationship between the stories — or the Bráses — is left poetically open, while the book builds to a powerful conclusion.

A different side of Brazil is presented in The Complete Stories of Clarice Lispector: while there’s irrationality here, it’s a modern, neurotic irrationality much more familiar to the European reader. There are a lot of stories here, and it was striking how the ones which I appreciated most are also the ones which the introduction focused on when I read it later. Not I think a testimony to my literary judgment so much as to the variation in quality. At her best though, Lispector was excellent:

“stroking his black hair as if stroking the soft, hot fur of a kitten”

“the daughter-in-law … plunked herself down … and fell silent… ‘I came to avoid not coming,’ shed’d said to Zilda”

“To my sudden torment, … he started slowly removing his glasses. And he looked at me with naked eyes that had so many lashes. I had never seen his eyes that, with their innumerable eyelashes, looked like two sweet cockroaches.”

“Any cat, any dog is worth more than literature.”

Budapest is even more literally a story of a Brazilian who seeks to become European, seduced by the challenge of learning Hungarian. It has a lot in common with the other Buarque novel I’ve read (Mein deutscher Bruder) — an unsympathetic narrator/protagonist, the speeded-up passage of time, and obsessions with language and thinly-characterised women.

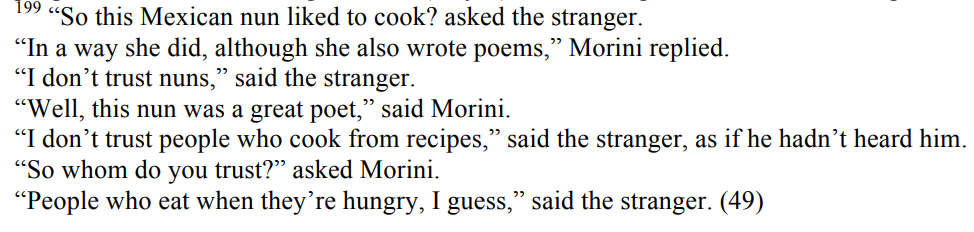

Speaking of thinly-characterised women, 2666. There was a lot to like in it, especially the first part, which was very M. John Harrisonian in its non sequiturs:

I’m not quite convinced though that there was 40 hours of my life-worth to like in it. Even bracketing out the Part About the Crimes, which by its nature concerns itself with misogyny, the other female characters (Elizabeth Norton, Rosa Amalfitano, Baroness von Zumpe) all feature mainly as sex objects. There is of course a lot to be said about the difference between the author’s attitudes and those of the society which he depicts….

Finally, one re-read: Sieben leere Häuser. I liked this much more on a second reading (and I liked it quite a lot the first time). The relationships and commonalities between the stories struck me much more (the kinds of emptiness, the relationships between parents and children). I’ve been occasionally comparing with Megan McDowell’s English translation, and found myself critiquing McDowell’s version against the “German original” — time to re-learn Spanish!

Next month is Black History Month (UK edition), although how much time Proust will leave me remains to be seen (The Prisoner/The Fugitive seems a substantial instalment).