A short month, with just eight books completed, but I managed to squeeze in my four German, one Portuguese, one graphic novel and one reread. The theme: sci-fi!

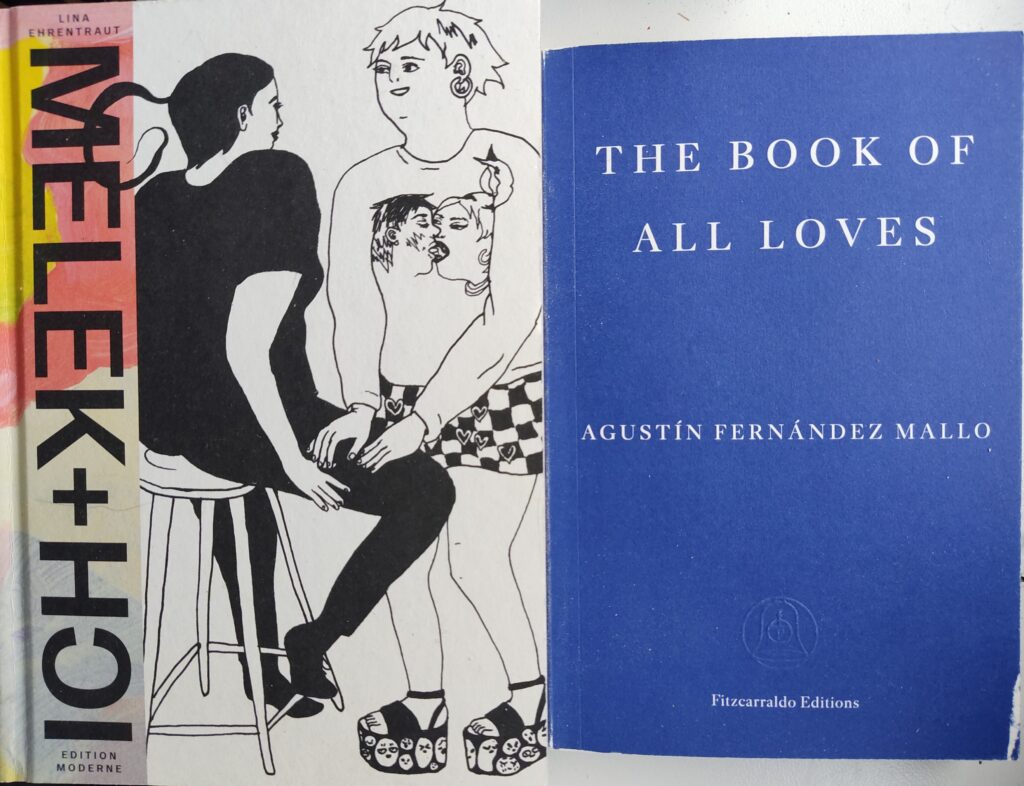

- Melek + Ich — Lina Ehrentraut

- Expect Me Tomorrow — Christopher Priest

- Grenzwelten — Ursula K. Le Guin (Autor), tr. Karen Nölle

- The Book of All Loves — Agustín Fernández Mallo, tr. Thomas Bunstead

- Der letzte Europäer — Martina Clavadetscher

- Europe in Winter — Dave Hutchinson

- Eine unberührte Welt Band 1 — Andreas Eschbach

- Raízes do amanhã: 8 contos afrofuturistas — Waldson Souza et al.

The graphic novel, Melek + Ich, was a great discovery. The back cover promised romance, SF, double identities, queer relationships, and narcisissism, all of which it delivered on. The art style was suitably grungy in its dive bars and messy flats, while bringing out the character(s) of the protagonist(s) effectively. The SF element was extremely soft, but consciously and amusingly so (“I happen to have invented a portal to parallel worlds”-style).

Grenzwelten combines two of Le Guin’s Hainish cycle: 1972’s The Word for World is Forest (this part was a reread for me), and The Telling from 2000. Both have a tendency to didacticism, especially in their loving portrayal of the traditional cultures on the respective worlds, but there is enough depth to the characters to keep them engaging.

Der letzte Europäer is a short play about a dog and a protective robot tussling over the last European of the title. It’s in Clavadetscher’s typical sort-of-verse style, though I found it much more obscure than her Knochenlieder. Now that I have some idea what was going on, I’d like to reread it before too long and see how much further in I get.

My search for actual German SF prose took me down several blind alleys: Der grüne Planet (Kai Focke et al.) is a collection of climate fiction short stories, some good (one about a generation ship which lands on a planet abandoned after a climate catastrophe had a nice line in grim humour), some (climate denialist) bad enough for me to stop reading. I get enough both-sidesing from the media already. Vakuum (Phillip P. Peterson) wasn’t awful, but too conventional and middle of the road (especially in its portraya of women) for me to want to invest the time to finish it. I ended up with Eine unberührte Welt Band 1 from the reliable Andreas Eschbach: Swabian humour put to good satirical use, especially in the story about government bureaucracy taking over the literary world.

Expect Me Tomorrow was Christopher Priest’s own venture into climate fiction. That element of the story is skilfully addressed, combining clearness about the actual events with an appreciation of why it could have looked different at the time of one strand of the story (that being the early 20th century). The obligatory Priestian twins link it to a true-life crime story, via a very ropey SF element which the flat prose manages to make believable. A good book to say goodbye to Priest with.

The other English-language novel, Europe in Winter, was the main reason for my choice of the month’s topic. I’ve been reading the Fractured Europe sequence in slow motion over several years, but Europe in Winter didn’t fit in with any of my recent themes. Now it set the theme, and it was great to dive back in to the world. In each book Hutchinson seems to take the story at least 90 degrees from where it was before, but our friend Rudi is always there to be our guide. This time he also repeated a scene word for word from the first book, which was a bold move, but justified for the story and also for being a fantastic scene. I was a bit slow reading the book because I kept reading bits out to myself, which I take to be a good sign.

The Book of All Loves is another Fitzcarraldo book, and keeps up that publisher’s tradition of boundary-pushing/oddness. The book has alternating sections: a catalogue of loves is interspersed with delphic statements from a pair of post-apocalyptic lovers; then there follow parts of a narrative about pre-apocalyptic lovers in Venice. I found this much the most interesting (due to the presence of a story), while the other parts were reminiscent of the Calasso-esque Eurowhimsy which I find attractive for a few pages, but then don’t finish.

Finally, Raízes do amanhã is a collection of Afrofuturist stories; I’d hoped that some would be from Lusophone Africa, but they’re actually all Brazilian. Like Melek + Ich, the SF elements are disarmingly super-soft: the inhabitants of a favela build a space station; the narrator’s aunt builds a time-machine, etc. Another common element is that of “spiritual sci-fi” — lots of vibrations, reminiscent of Doris Lessing’s Canopus in Argus books. My woo-ometer was tested at times, but there was enough variety for me to enjoy almost every story in the book.

Next month is another Lusophone month: a few books which will be covered by the Portuguese in Translation group this year, plus a graphic novel from Portugal and whatever else comes my way….