Just eight books finished last month, though I made progress with quite a few that should be completed in April (mostly for my planned non-fiction theme). I missed my targets for women/POC (three out of eight), and German (three); on the other hand, there’s one graphic novel, one re-read, two (2) Portuguese books, and six of the eight belong to my month’s theme of Lusophone writing.

- Weltuntergang fällt aus — Jan Hegenberg

- A Bicicleta Que Tinha Bigodes — Ondjaki

- The Word Tree — Teolinda Gersão, tr. Margaret Jull Costa

- Ich Ich Ich: Selbstzeugnisse und Erinnerungen von Zeitgenossen — Fernando Pessoa, tr. Inés Koebel

- The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis — Lydia Davis

- Balada para Sophie — Filipe Melo

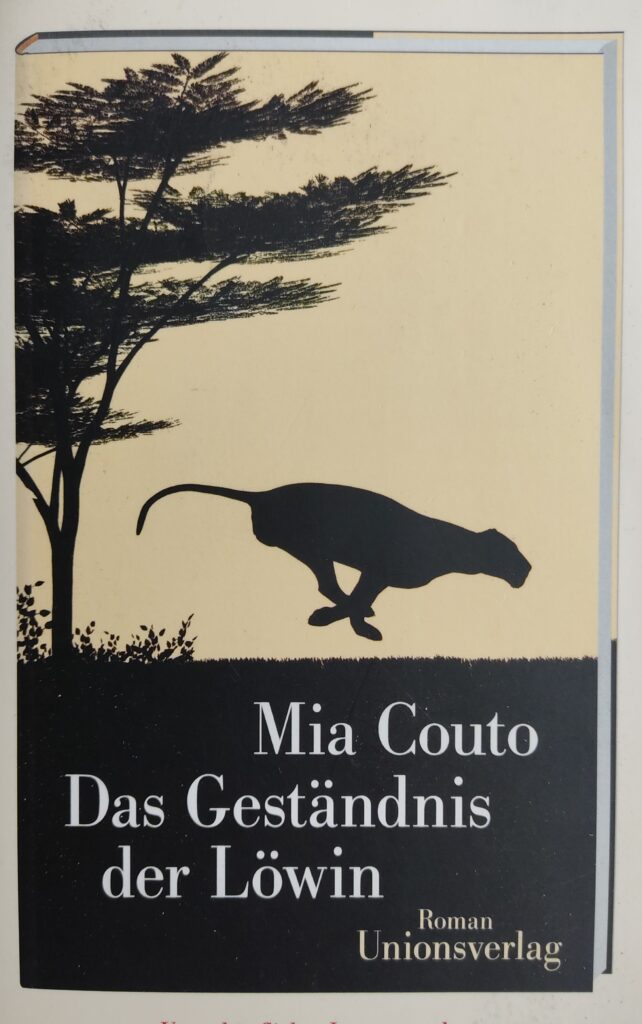

- Das Geständnis der Löwin — Mia Couto, tr. Karin von Schweder-Schreiner

- The Double — José Saramago, tr. Margaret Jull Costa

Starting with the Lusophonians, A Bicicleta Que Tinha Bigodes (Angola) was my re-read; I was able to read it a bit more fluently this time, so I had a better sense of the book as a whole, but otherwise there’s nothing new to say: it’s a lovely piece of childhood magical realism, in the kind of middle-class African setting I tend to hear relatively little about.

Das Geständnis der Löwin (Mozambique) has similar elements, but woven into a dreamlike narrative which is constantly taking surprising turns. It’s one which I definitely should reread to try to piece together a bit more, but even on a first reading there’s a lot to appreciate: the twists relate to depths in the characters, while Couto is able to present different perspectives to show each character fairly (except perhaps the Couto-esque journalist). (One of the books which I didn’t finish is Paulina Chiziane’s The First Wife, set in the very different Mozambique of Maputo).

The Word Tree (Portugal) is also set largely in Mozambique — or rather in Lourenço Marques, the capital of the Portuguese colony. It focuses on the life of a young woman growing up more in tune with the black culture than with her own dysfunctional family, but the stand-out section is the middle part, which shows the experiences of her mother in Portugal and in Mozambique, with sympathy, but without special pleading.

Ich Ich Ich (Portugal) is a collection of writings by (and a few about) the great, weird, Fernando Pessoa, who saw the beginnings of the Salazar dictatorship which loomed over the characters in The Word Tree. Some of it was, I must say, hard-going — a lot of self-psychoanalysis and mysticism which is not very interesting in itself, though it does shed light on the obvious central issue of his heteronyms, the alter egos which he created for his writing (and, less successfully, for interactions with his friends and girlfriend). The heteronyms seem to represent extremes of different aspects of his character, which makes me somewhat skeptical of the likely quality of their verse, but I’ll be happy to be disproved.

The Double (Portugal) is in some respects typical Saramago: pages-long paragraphs, with dialogue nested inside, create a distinctive texture which in this case I found quite approachable; there’s a lot of comedy, and the dialogues in particular are nicely judged. Saramago applies to idea of the doppelganger to contemporary Portugal and explores the consequences for the characters, which works brilliantly in the first part of the book. Unfortunately the second half takes a much darker turn, for reasons which the narrator himself admits being unable to explain. In this case, though, rather than defusing the issue, this comes across as an admission of authorial defeat.

Balada para Sophie (Portugal) was the month’s graphic novel, which (on a linguistic note) I was pleased to be able to read without assistance other than looking up a few words. It’s an enjoyable, but not earth-shattering story of a one-sided rivalry between two pianists who grow up during the German occupation of France; the art again is not groundbreaking, though I enjoyed the cat (easily pleased).

Lydia Davis’ Collected Stories are occasionally baffling, but overall extraordinarily good – she manages to do so much in so little space. Some almost randomly chosen moments of brilliance:

If I believed that what I felt was not the center of everything, then it wouldn’t be, but just one of many things, off to the side, and I would be able to see and pay attention to other things that were equally important, and in this way I would have some relief.

so often, in the case of other subjects, he is not terribly interested in what I say to him, especially when he sees that I am becoming enthusiastic.

In their eyes, her every gesture could now be called senile. Even quite normal behavior seemed mad to them, and nothing she did could reach them.

Finally, a non-fiction taste of next month: Weltuntergang fällt aus is a splendid account of the energy transformation needed to rein in global heating. It’s focused on Germany, but the broad outline will apply to any other developed country, at least. There are a lot of numbers, but Hegenberg keeps it accessible with lots of jokes and an engagingly informal style. The combination of these can grate after a while, so I wouldn’t read it straight through, but taken in moderate doses it left me better informed and a teeny bit optimistic.