A good start to the year: I finished eleven books this month, six by women/POC, four in German, one in Portuguese — all according to plan. My project for the month was to read Fitzcarraldo authors (not necessarily Fitzcarraldo editions) — eight of the eleven were part of that. My other longer-term plan is to read Europe, or at least the EU — this time I covered:

- Germany

- Sweden

- Poland

- Italy

- France

and non-EU Norway and UK. (Accidentally all but one of the books are either translated or in languages other than English).

- Clemens Meyer über Christa Wolf — Clemens Meyer

- OpOs Reise — Esther Kinski

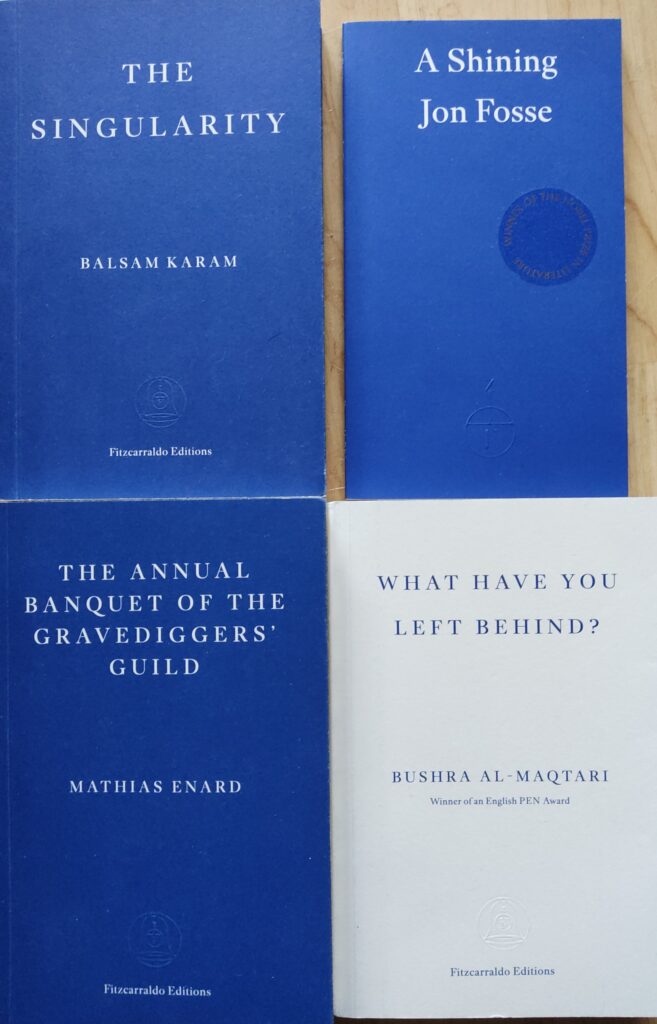

- The Singularity — Balsam Karam, tr. Saskia Vogel

- Anos de chumbo e outros contos — Chico Buarque

- Anna In — Olga Tokarczuk, tr. Lisa Palmes

- Die Geschichte der getrennten Wege — Elena Ferrante, tr. Karin Krieger

- The Annual Banquet of the Gravediggers’ Guild — Mathias Énard, tr. Frank Wynne

- What Have You Left Behind? — Bushra al-Maqtari, tr. Sawad Hussein

- Minor Detail — Adania Shibli, tr. Elisabeth Jaquette

- A Shining — Jon Fosse, tr. Damion Searls

- The Sandman Vol. 9: The Kindly Ones — Neil Gaiman

Starting with the true Fitzcarraldi, The Singularity (by Kurdish Swede Balsam Karam) is just out, and is a perfect blend of content and form. The Prologue was somewhat off-putting — it doesn’t hold your hand by gently introducing you to the characters — but it establishes the link between the two protagonists who are respectively the focus of the first and third main sections, while the second is based on the intersection of their experiences. This part in particular uses formal innovation very effectively to show the connection between the two, while the anonymisation gives the book a universal significance.

The “Middle-eastern Women” sub-project continued with What Have You Left Behind? (Bushra al-Maqtari, Yemen). I started this a while ago, but had to read it in short stints; as the back cover says, it’s “As difficult to read as it is to put down”. It’s composed, Svetlana Alexievich-style, of testimonies from relatives of victims of the war in Yemen (now worsened by British and American bombing, which is one of the factors that prompted me to finish it). It’s absolutely remorseless: both sides in the conflict target civilians indiscriminately, and each testimony ends with the full names and ages (typically young) of the victims. While each victim’s story ends in much the same way, what stands out is the diversity of their lives before they were cut short. This humanisation of the victims makes the book worth reading despite the harrowing content.

Minor Detail (Adania Shibli, Palestine) again has links to current affairs: not only does it centre on war crimes in the foundation of Israel, Shibli was famously disinvited to receive a prize in Germany because of the political implications of her book (as misread by German critics). The first part details, in (again, the only word I can use) remorseless, flat prose, a war crime which took place in the Negev desert in 1949. The second is a first-person narration of a Palestinian women investigating the event, detailing the bureaucratic and violent effects of the apartheid system. The rhymes between the two stories create the book’s lasting impression that everything changes, while everything stays the same.

Returning to Europe, The Annual Banquet of the Gravediggers’ Guild (Mathias Énard, France) is an entertaining beast of a novel: almost 500 pages, it centres (“focuses” is hardly the word) on an anthropologist who moves from Paris to western France to study the “natives”. Énard takes this as a starting point to tell the stories firstly of the local people, and (by reincarnation) the history of the area. The central banquet is particularly, and explicitly, Rabelaisian, and represents the book’s extreme of fantasy; the anthropologist’s own story is essentially realistic, but somewhat under-motivated. As with many other works from this otherwise great publisher, there are many proofreading errors, but they’re not such as to spoil the experience.

At the opposite end of pretty much every scale, A Shining (Jon Fosse, Norway) is barely even a novella, but focuses entirely on the perceptions of the protagonist. This ultra-subjectivity just about makes the spiritual experiences possible to swallow for the unreligious reader, but it’s not where I’d recommend starting with Fosse (that would be Aliss at the Fire, for a brief introduction).

Turning to non-Fitzcarraldo Fitzcarraldans in German: Clemens Meyer über Christa Wolf (Clemens Meyer, Germany) is a short, but dense subjective round-up of East German literature, through the medium of Meyer addressing a bust of Wolf at his desk. There were a lot of new names for me, which was an occasional impediment, but Meyer is able to draw brief, rounded portraits of the work and the personalities (especially the personalities — he refers several times to the “soap opera” of the literary world) which leave the reader wanting to read more of their books (especially Wolf’s).

OpOs Reise (Esther Kinski, Germany) is a children’s book — not my usual fare, but I wanted to read something by Kinski, and the premise of a school of pilot whales living their lives off the coasts of Scotland and Essex was intriguing. There’s a satisfying blend of humour and pathos which made it an hour well spent.

Anna In is by Kinski’s former translatee Olga Tokarczuk (Poland), and has been translated by both Kinski and (for this edition) Lisa Palmes. It’s very odd indeed: Tokarczuk retells the Sumerian myth of Inanna in a cyberpunk setting (with hints of Discworld), with multiple narrators offsetting the monumentality which you might expect from a tale of gods and the underworld.

My fourth German book was part three of the Neapolitan novels of Elena Ferrante (Italy) — Die Geschichte der getrennten Wege. It’s a bit shorter and more focused than the sprawling second volume, which was welcome, but as the title implies, we see less of the most obviously interesting character of Lila in this one. Lenu, meanwhile, seems to become more and more amorphous: it’s fascinating to try to judge the reliability of her narration. As with the Gravedigger’s Banquet, I found the main plot twists psychologically obscure, but is this due to Lenu’s or Elena’s storytelling?

Portuguese book of the month was Anos de chumbo e outros contos (Chico Buarque, Brazil). Not easy — the YA-type books I’d read before had somewhat overinflated my confidence, while Buarque has a substantial vocabulary (seeming to include a remarkable number of words for grunting and pushing). I was able to decipher it though, and enjoyed the typical Buarquian touches — stealthy passages of time, bizarre twists, and social engagement.

Finally, graphic novel of the month was The Sandman Vol. 9: The Kindly Ones (Neil Gaiman, UK — mostly). While it had seemed in the recent volumes that the story had broken down to focus less on on Morpheus and more on side-characters, it turns out that he had a plan all along, and in this bumper issue, (almost) all was tied up. Extra points for high raven content.

Next month is science fiction month. A short one, sadly, but I’ve got some crackers I’d like to get through….