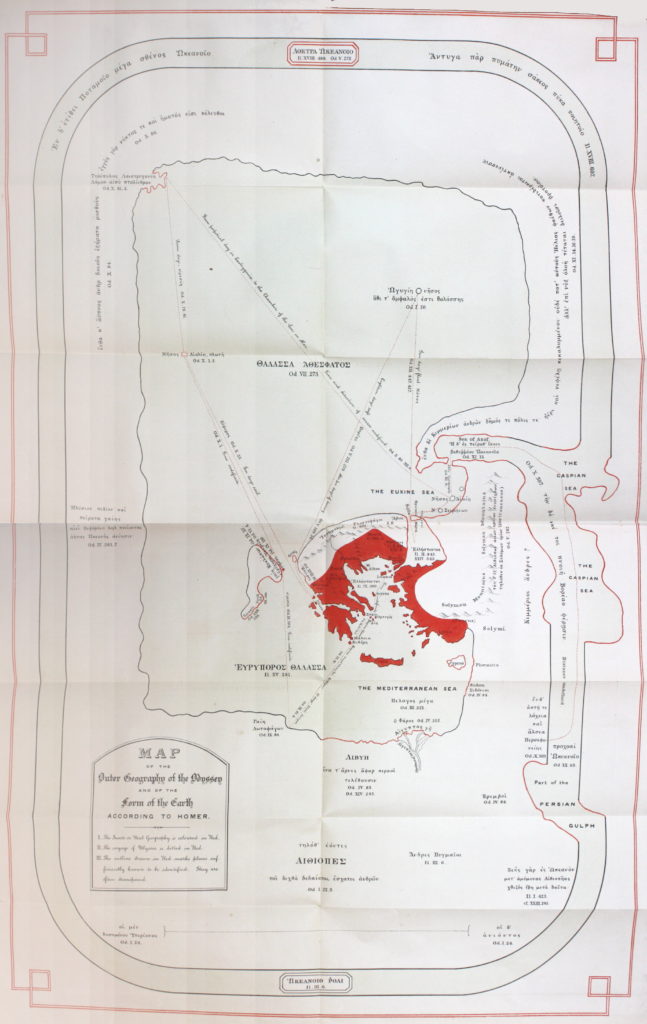

Recently, the third and concluding volume of Gladstone’s Homer and the Homeric Age finally made it to Project Gutenberg. The scanned versions available online all failed to include a map which was inserted at the end of the volume, showing Gladstone’s view of Homer’s view of the world. A splendid map it is too:

Obtaining a scan of the map took quite some time, accounting for the delay, but the preparation of the text itself also involved a lot of work from many people. Each page was checked five times to ensure accuracy and to replicate the formatting of the original, and this process also involved transcription of all the Greek, prior to its reconversion to Greek script in the final book. The electronic version incorporates 71 corrections, many of those being Greek typos spotted by the three volunteers who read through the book after I’d finished with it (or thought I had). This number of corrections is more or less typical for a book of this size, so I’m pretty confident our ebooks are more accurate than the original printed versions.

The whole project started with volume 1 in November 2013, after I’d read an account of Gladstone’s weird and wonderful theory of colour in Homer in Guy Deutscher’s Through the Language Glass: Why The World Looks Different In Other Languages — one book which I’m still to finish. The theory being, incidentally, that “the organ of colour and its impressions were but partially developed among the Greeks of the heroic age”, due to the lack of colour in their environment:

The olive hue of the skin kept down the play of white and red. The hair tended much more uniformly, than with us, to darkness. The sense of colour was less exercised by the culture of flowers. The sun sooner changed the spring-greens of the earth into brown. Glass, one of our instruments of instruction, did not exist. The rainbow would much more rarely meet the view. The art of painting was wholly, and that of dyeing was almost, unknown; and we may estimate the importance of this element of the case by recollecting how much, with the advance of chemistry, the taste of this country in colour has improved within the last twenty years. The artificial colours, with which the human eye was conversant, were chiefly the ill-defined, and anything but full-bodied, tints of metals. The materials, therefore, for a system of colour did not offer themselves to Homer’s vision as they do to ours. Particular colours were indeed exhibited in rare beauty, as the blue of the sea and of the sky. Yet these colours were, so to speak, isolated fragments; and, not entering into a general scheme, they were apparently not conceived with the precision necessary to master them.

Other recently completed projects include Otto Jespersen’s Language, in which he uses his impressive range of reading to outline the state of linguistics at the time (early 20th century), with a focus on the development of language as a whole — historically — and in the individual. On the way, he hints at some interesting views on language learning:

There is a Slavonic proverb, “If you wish to talk well, you must murder the language first.”

(Or as I’ve also heard it: “To be a wit, you must first be a halfwit”.)

one should not merely sprinkle the pupil, but plunge him right down into the sea of language and enable him to swim by himself as soon as possible, relying on the fact that a great deal will arrange itself in the brain without the inculcation of too many special rules and explanations.

His How to Teach a Foreign Language should be leaving DP soon, so there’ll be more where that came from.

Light relief was provided by Dion Boucicault’s The Colleen Bawn: not of the highest literary merit, but some interesting background to Joyce.

Pleased to hear you’ve got it done!