Through a combination of accident and design, our Scottish journey intersected with several literary sites.

Our main target on the trip was the Cairngorms, at more or less the centre of which are the Pools of Dee:

At the time I was reading over Volume 2 of Gladstone’s Homer and the Homeric Age, which I’ve just finished for Distributed Proofreaders. He was also keen to see the pools, as reported by Nan Shepherd in The Living Mountain:

At the time I was reading over Volume 2 of Gladstone’s Homer and the Homeric Age, which I’ve just finished for Distributed Proofreaders. He was also keen to see the pools, as reported by Nan Shepherd in The Living Mountain:

One of the truest hill-lovers I have known was old James Downie of Braemar, whose hand-shake (given with a ceremonial solemnity) sealed my first day on Ben MacDhui. Downie had once the task of guiding Gladstone to the Pools of Dee, which the statesman decided must be visited. Now the path to the Pools, from the Braemar end, is long though not rough, shut in except for the mountain sides of the Lairig Ghru itself; and the Pools lie beneath the summit of the Pass, so that to see the wide view open on to Speyside and the hills beyond, one must climb another half mile among boulders. Gladstone refused absolutely to stir a step beyond the Pools. And Downie, the paid guide, must stop there too; an injury which Downie, the hillman, never forgave. Resentment was still raw in his voice as he told me about it, forty years later.

The view Gladstone never saw:

On the way south, we passed through Dunkeld, where Gawin Douglas was bishop (some years after completing his version of the Æneid).

Scone features heavily in The Bruce and The Wallace, though little remains from those times. There is an interesting arboretum, with the original Douglas Fir, brought back by David Douglas, and some baby redwoods:

Another recent project, Scottish Poetry of the Sixteenth Century, was closely associated with Linlithgow palace. The Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis was performed in this hall:

Another recent project, Scottish Poetry of the Sixteenth Century, was closely associated with Linlithgow palace. The Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis was performed in this hall:

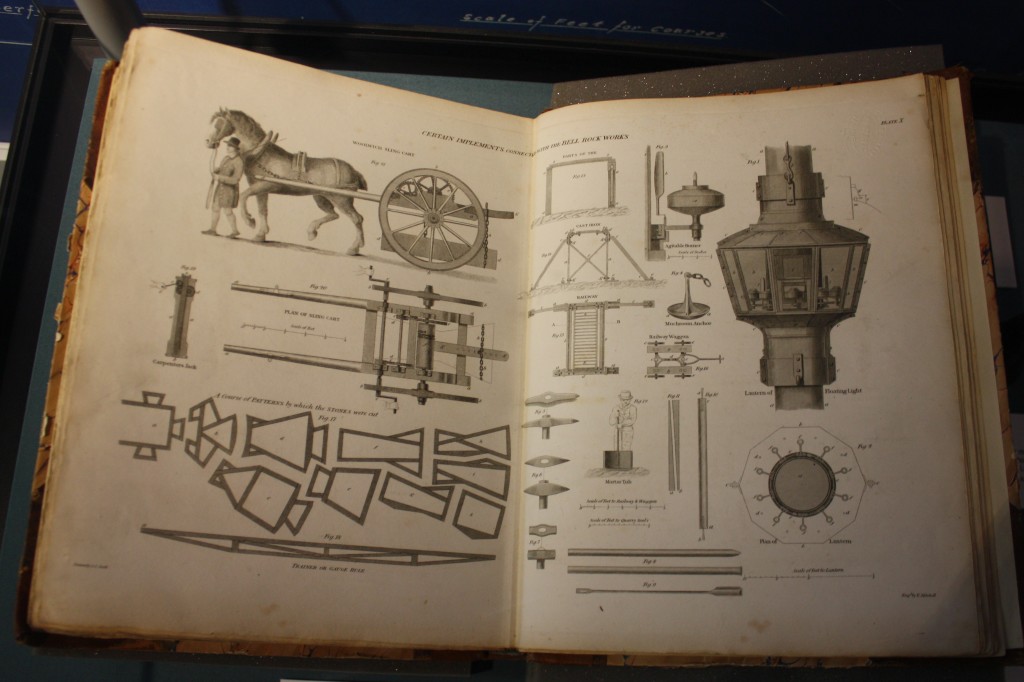

In Arbroath, a museum tells the story of the Bell Rock Lighthouse. There are models of the construction process:

And an original text of Stevenson’s account. In the top-left of this page is Bassey, the horse which moved the stones which became the lighthouse:

And an original text of Stevenson’s account. In the top-left of this page is Bassey, the horse which moved the stones which became the lighthouse:

And in St Andrews, we visited her in the flesh (almost):