I finished 11 books this month: nine for my theme of the month (non-fiction), and seven by women/POC, three in German, and one in Portuguese.

- Mekka hier, Mekka da — Melina Borčak

- What is Mine — José Henrique Bortoluci, tr. Rahul Bery

- There’s a Monster Behind the Door — Gaëlle Bélem, tr. by Karen Fleetwood and Laëtitia Saint-Loubert

- Diário de uma volátil — Agustina Guerrero, tr. Marcelo Barbão

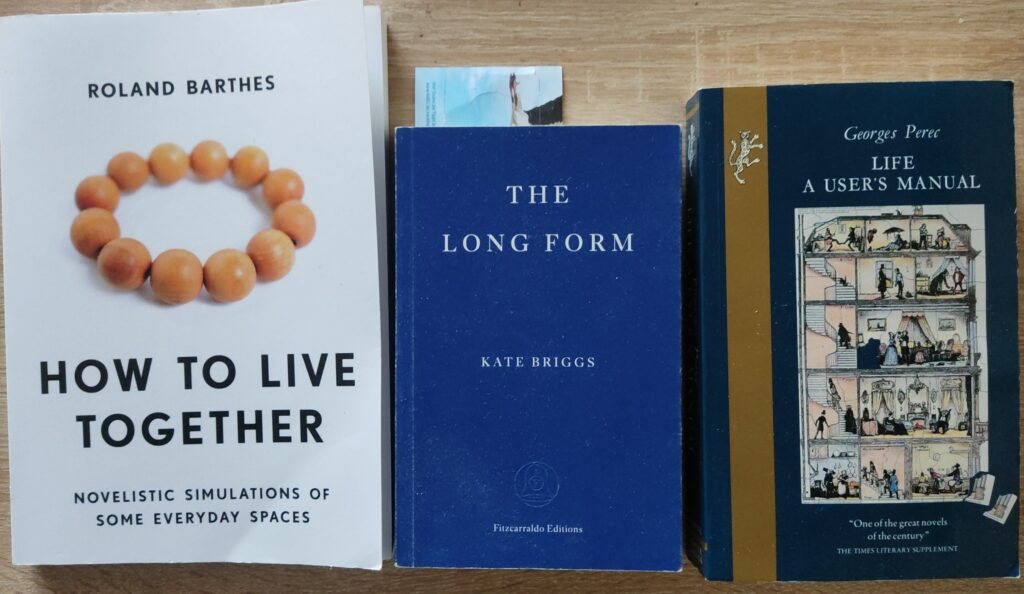

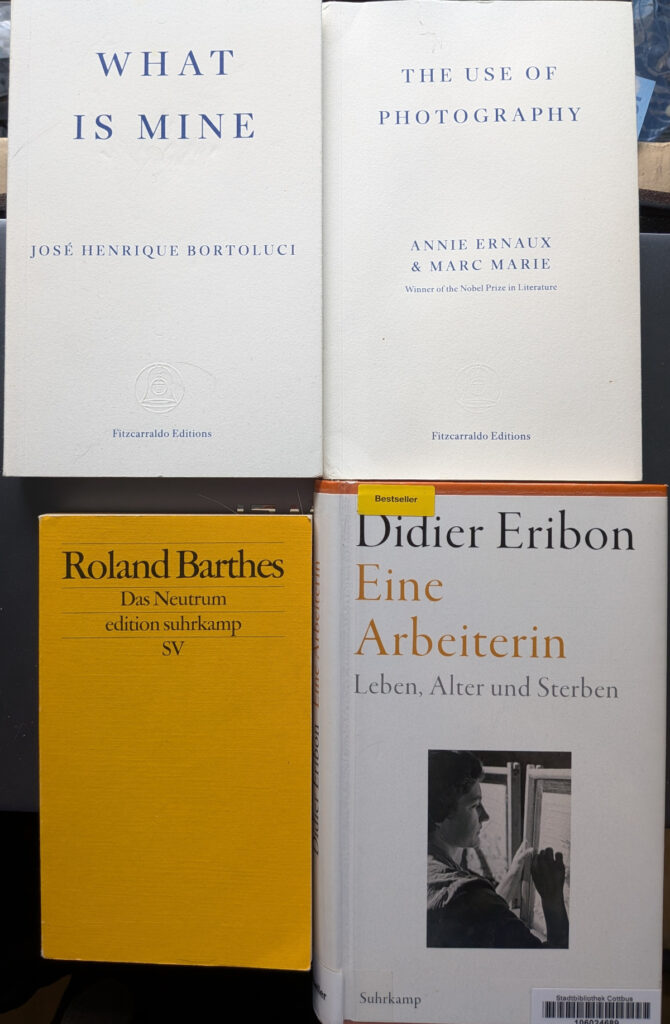

- The Use of Photography — Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, tr. Alison L. Strayer

- Your Utopia — Bora Chung, tr. Anton Hur

- Das Neutrum — Roland Barthes, tr. Horst Brühmann

- Eine Arbeiterin: Leben, Alter und Sterben — Didier Eribon, tr. Sonja Finck

- Arabs: A 3,000-Year History of Peoples, Tribes and Empires — Tim Mackintosh-Smith

- The Language of the Night: Essays on Writing, Science Fiction, and Fantasy — Ursula K. Le Guin

- Free — Lea Ypi

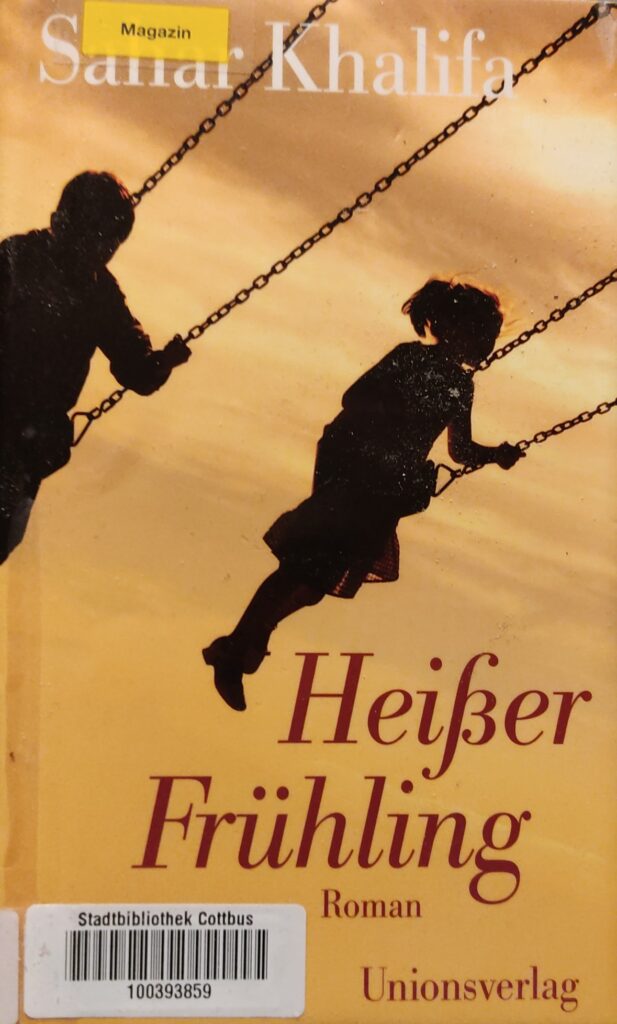

A couple of sub-themes popped up accidentally: four of the books are French (if one includes Réunion), and two have cancer as a main topic. So I start with The Use of Photography, an odd but surprisingly rewarding book in which Annie Ernaux (and her lover) write about their relationship, based on photographs of the piles of clothes they removed before having sex (as she writes, “I don’t expect life to bring me subjects but rather unknown structures for writing.”). Ernaux simultaneously explores a contrasting aspect of her physicality, her treatment for breast cancer during this period. It’s intriguing to see her choice of carpets and mules, but the real wonder is her ability to transform this very specific time and space into universally significant art.

The other cancer text is one of the reasons for my choice of topic, What is Mine, which was the subject of the Portuguese in Translation book group. Bortoluci writes about his father, a Brazilian truck driver of the 1970s and ’80s, now also dealing with cancer. To make it even more Ernauxian, Bortoluci is a first-generation graduate and academic, culturally separated from the world of his father. He conveys brilliantly the epic side of the father’s life, in a time when truck drivers were like Brazil’s cowboys opening up the wild west, while drawing out the parallels between the cancer and the rapacious development encouraged by successive governments in the country.

Another French book was the other spur for the theme: Das Neutrum is the second of the three series of lectures Barthes delivered at the Collège de France and published in note form. I confess to feeling I’d tied one hand behind my back by deciding to read it in German: most of the day to day topics were accessible enough, but I did struggle with the more abstract aspects. It wasn’t always clear to me exactly how each of his sub-topics related to the idea of the neutral, but the overall theme of nuance and avoiding binary oppositions was very attractive and is obviously very relevant today. More more thoughts from myself and other readers, see the Bluesky posts for #AContinuation25 .

Eine Arbeiterin: Leben, Alter und Sterben is another French book in German, also dealing with ageing and dying, and also by an academic who escaped — not too strong a word in this case — his working class origins. As in Returning to Reims, Eribon is brilliant at combining an unflinching look at his own experiences, and his own failings, with a philosophical and social analysis of the themes involved. I’m now impatient to read Foucault, Beauvoir, and the other authors he discusses.

The only novel this month was the last French book, There’s a Monster Behind the Door, left over from last month’s International Booker theme. It’s a very colourful portrait of life on Réunion, where the actual story is a very shoogly hook on which to hang the descriptions. These are sometimes excellent:

Of course, his mother had been a girl, as had his grandmother and his wife too – to some extent – but that didn’t mean that history should repeat itself. ‘Thundering typhoons!’ he swore, wiping his arms. A pit bull, fine; a baby giraffe, fine; a three-legged horse or big cockroach, fine … but a girl! It’s like rearing a child who’s not right in the head! And all because they had wanted to save twenty francs on an ultrasound!

sometimes not:

this murmur violently plunged me into an arid and unknown atmosphere in which a dense plume of sadness arose in small wafts

but the enthusiasm of the writing was enough to keep me happily reading.

I still read a short story a day this month, and finished Your Utopia. Mostly satirical SF stories with a social aspect, I was grateful for the author’s note at the end which explained the genesis of some of them. The humour is rather broad and there are some uncharacteristic translation flubs from Anton Hur; Cursed Bunny might have been a better place to start with her.

Non-fiction SF, The Language of the Night: Essays on Writing, Science Fiction, and Fantasy is fantastic. The idea of a book of essays is often off-putting, but Le Guin’s are always clever, funny, and thoughtful:

The poet Rilke looked at a statue of Apollo about fifty years ago, and Apollo spoke to him. “You must change your life,” he said.

When the genuine myth rises into consciousness, that is always its message. You must change your life.

The modern literary cliché is: Bad people are interesting, good people are dull. This isn’t true even if you accept the sentimental definition of evil upon which it’s based; good people, like good cooking, good music, good carpentry, etc., whether judged ethically or aesthetically, tend to be more interesting, varied, complex, and surprising than bad people, bad cooking, etc.

This is a varied collection mostly of speeches and introductions to some of her books, but they’re well-selected to show their common themes (particularly, a justification for SF to be treated as seriously as other genres). Several decades on, it’s safe to say there’s been some progress, but not enough to make the book irrelevant.

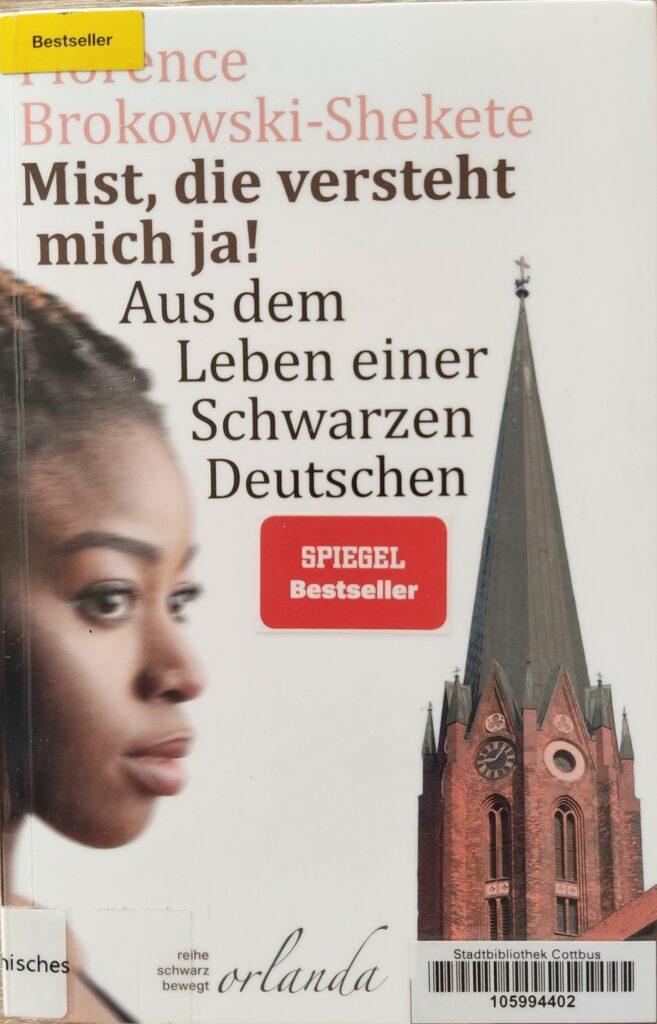

The last German book this month, Mekka hier, Mekka da is an entertainingly potty-mouthed guide for Germans on how to be less racist. Once again, a very timely subject! Borčak draws particularly on her own experience as a Bosnian in Germany, concluding with a chapter on genocide which is particularly important given the continuing German support for the genocide in Palestine.

Palestine unsurprisingly features heavily towards the end of Arabs: A 3,000-Year History of Peoples, Tribes and Empires; the book was written in 2019, so its conclusion is a fascinating illustration of how things have changed since then — occasionally for the better (Assad), but overwhelmingly not. There’s much more to Arab history than that, of course, and this is a very entertaining as well as informative account. Often both are combined, as when we find out that Arabic has words for each space between the different fingers for the hand, and for the droppings of different species of birds. The author frequently refers to his own life in Yemen as illustration (he’s since been forced to leave), but his enthusiasm and understanding of the people are clear throughout this unavoidable long book. He’s very fond of alliteration and rhyme, both in his own prose and in his slightly questionable poetic translations, but it all keeps things moving along splendidly.

Diário de uma volátil wasn’t a great choice, I have to say — I wanted a non-fiction “graphic novel” in Portuguese, which this is, and it was nice to read something with minimal support, but the book itself (an Argentinian cartoon Bridget Jones, essentially) was not really for me.

The last book of the month, Free, is fantastic. It brings home what life was like in the last days of communist Albania, amazingly close in space and time, but incredibly distant socially and economically. With poetically good timing, Ypi synchronised her teenage years with the unstable years which followed, with losses of innocence on all sides. There’s a great balance of humour and affection, along with the unavoidable darkness.

Next month is another finishing-off month: Animal Joy (Nuar Alsadir), which I didn’t quite finish for this month, is a cracker, and I have lots of others which I was enjoying, but paused with for one reason for another. I may also extend “finishing off” to some series….