I finished approximately eleven books this month (counting a series of standalone stories as one): seven by women/POC, and seven also as part of project sacre bleu, my exploration of French literature.

- Just Out of Jupiter’s Reach — Nnedi Okorafor, Falling Bodies — Rebecca Roanhorse; The Long Game — Ann Leckie; Void — Veronica Roth

- A Girl’s Story — Annie Ernaux, tr. Alison L. Strayer

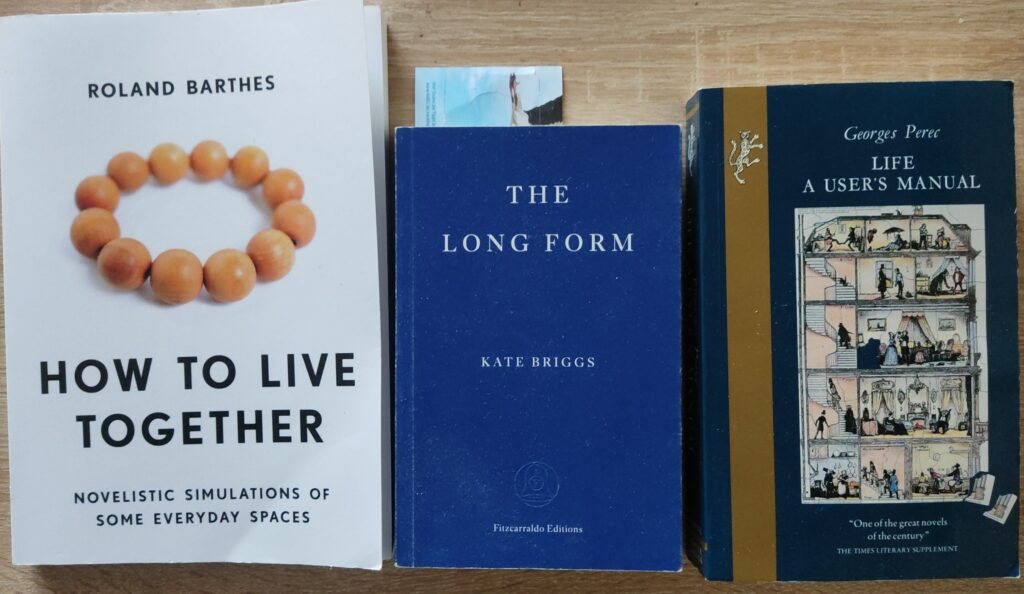

- How to Live Together — Roland Barthes, tr. Kate Briggs

- The Black Incal — Alejandro Jodorowsky and Mœbius, tr. Justin Kelly

- The Long Form — Kate Briggs

- Antichristie — Mithu Sanyal

- Ahnen — Anne Weber

- Contos de Lima Barreto — Lima Barreto

- Schnell, dein Leben — Sylvie Schenk

- Life A User’s Manual — Georges Perec, tr. David Bellos

- Returning to Reims — Didier Eribon, tr. Michael Lucey

Starting with those stories, I was inspired by reading the Scalzi story last month to continue with four more in the series (all by women). The Okorafor confirmed my judgment that I don’t need to read more of her, which is a plus, while the other three were all at least enjoyable. Void was the standout for me, combining an interesting premise (non-instant interstellar travel) with a satisfying murder mystery.

Other non-French books included Antichristie (Deutscher Buchpreis nominated and by the splendid Mithu Sanyal, both good recommendations), which was an absolute hoot. Agatha Christie, Sherlock Holmes, Doctor Who and the dead queen Elizabeth all play substantial roles, but at its core this is a book about the Indian independence movement and the role in it of Vinayak Savarkar (new to me). It’s a bit overlong, with a few too many time travel gags, but generally great fun as well as educational.

My short stories and Portuguese book for the month were the Contos de Lima Barreto, which I found rather hard-going. Linguistically they were I think a bit antiquated — good for my vocabulary at least, if I ever come across the words again — and in terms of the content also quite dated. They’re satires of a particular period in Brazilian history which I didn’t find particularly grabbed me from my perspective today.

The Long Form was one of two re-reads, this time as part of the group read of Briggs and Barthes. Reading it along with the other book was a great experience, really bringing out the way that Briggs explores the ideas in Barthes and uses them to devlelop the story.

The first French book, then, and one of the main reasons for the month’s topic, was How to Live Together. Slightly off-puttingly at first, Barthes doesn’t organise his material as part of an argument, instead presenting each topic in alphabetical order. The advantage of this is that the readers can fill in the blanks themselves, and I did find myself thinking about his ideas not just while reading the Briggs novel, but with the other books this month as well.

The other reason for the monthly topic was that I was going to two plays adapted from French memoirs. The first, A Girl’s Story, was the second re-read, and I loved it just as much the second time. Ernaux looks at her past self with just the right balance of empathy and estrangement to present a convincing portrait of “the girl of ’58”.

She is an outsider, as in the novel by Camus that she reads in October, galumphing, moist and sticky amidst the pink-smocked girls, their well-bred innocence and unsullied sexes.

But what is the point of writing if not to unearth things, or even just one thing that cannot be reduced to any kind of psychological or sociological explanation and is not the result of a preconceived idea or demonstration but a narrative: something that emerges from the creases when a story is unfolded and can help us understand — endure — events that occur and the things that we do?

It is the absence of meaning in what one lives, at the moment one lives it, which multiplies the possibilities of writing.

Returning to Reims is a fascinating counterpoint to the Ernaux: Eribon is from a similar region of northern France, working class, but with the added complication (for the time and place) of being gay. The hook for the book is his return to the region after his father’s death, out of which he tells his own story of leaving his class and embracing his sexuality, seen through the lens of Bordieu’s and Foucault’s ideas. The intellectual discussions are illuminating, and added several books to my TBR list!

There is a way in which my daily life is now haunted by Alzheimer’s — a ghost arriving from the past in order to frighten me by showing me what is still to come. In this way, my father remains present in my existence. It seems a strange way indeed for someone who has died to survive within the brain — the very place in which the threat is located — of one of his sons.

Selection within the educational system often happens by a process of self-elimination, and that self-elimination is treated as if it were freely chosen: extended studies are for other kinds of people, for “people of means,” and it just happens that those people turn out to be the ones who like going to school.

People know that things are different elsewhere, but that elsewhere seems part of a far off and inaccessible universe. So much so that people feel neither excluded from nor deprived of all sorts of things because they have no access to what, in those far off social realms, constitutes a self-evident norm.

Even the very word “inequality” seems to me to be a euphemism that papers over the reality of the situation, the naked violence of exploitation. A worker’s body, as it ages, reveals to anyone who looks at it the truth about the existence of classes.

An interest in art is something that is learned. I learned it…. An interest in artistic and literary objects always ends up contributing, whether or not it happens consciously, to a way of defining yourself as having more self-worth.

This observation of Sartre’s from his book on Genet was key for me: “What is important is not what people make of us but what we ourselves make of what they have made of us.”

I’ve had a copy of Life A User’s Manual for perhaps 30 years now, and finally got round to reading it. It turned out to be the perfect time, as it went particularly well with the Barthes. Like the Zola novel “Pot Luck” which Barthes discusses, the book is set in a Parisian apartment building, with chapters set in each room in turn telling the stories of the occupants and their relationships. It toys with the reader’s patience at times (there are many, many descriptions of the furniture and pictures in the various rooms), but it juxtaposes these with plenty of fun stories. The central thread draws the book together in a satisfying way.

Graphic novel (ish — part 1 of 6) was The Black Incal; also French-ish, (written by a Chilean, but drawn by the French Mœbius). While reading, I realised that it’s basically The Fifth Element (not a bad thing), which turns out to have been the basis of a legal saga.

Finally, another good pair, this time of French-German/German-French authors. Ahnen is an exploration by Anne Weber of her great-grandfather’s, and to a lesser extent other ancestor’s lives. In a recurring theme for this month, there’s a blend of story and ideas which she carries off well, though I can’t say I enjoyed it as much as her fiction.

Schnell, dein Leben is intriguing: written in the second person, present tense, it certainly involves the reader very directly (enhanced, not entirely advisedly, by the style of the audiobook’s narration). The story itself is based heavily on various coincidences, but its exploration of recent history is timely.

Next month is basically Palestine (building on #ReadPalestineWeek), though I may divert into Arabic/Middle East more generally if it all gets too much. Also starting the group read of Tom Jones, and I may finish volume 1 of Der Zauberberg in the anniversary year….