I finished reading ten books this month — just four for my usual diversity goal of women/POC, but eight for my monthly reading topic (LGBT+), three in German, and two (2) in Portuguese.

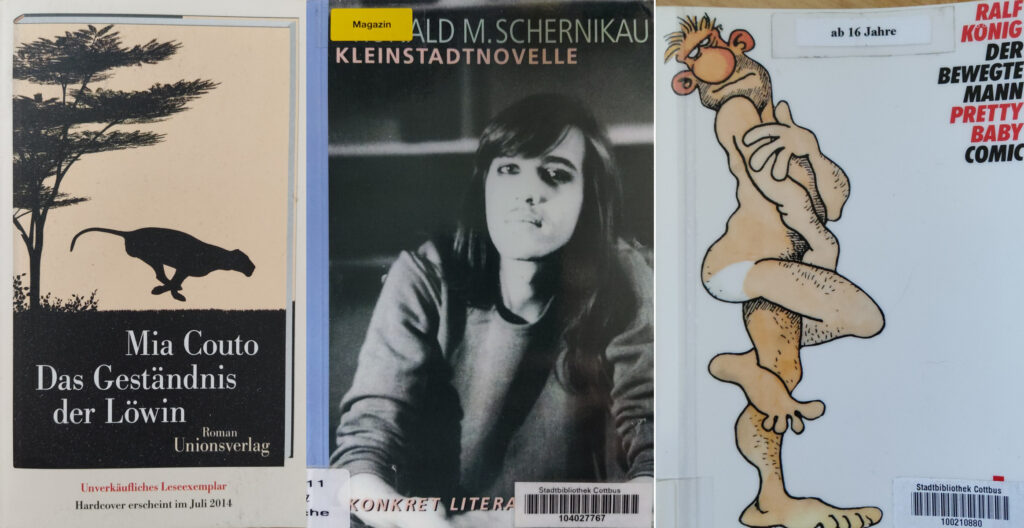

- Kleinstadtnovelle — Ronald M. Schernikau

- Das Geständnis der Löwin — Mia Couto, tr. Karin von Schweder-Schreiner

- The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House — Audre Lord

- Night Side of the River — Jeanette Winterson

- Um milhão de finais felizes — Vitor Martins

- The Death of Vivek Oji — Akwaeke Emezi

- Der bewegte Mann | Pretty Baby — Ralf König

- Shuggie Bain — Douglas Stuart

- Uma menina está perdida no seu século à procura do pai — Gonçalo M. Tavares

- The Female Man — Joanna Russ

Starting with the LGBT books, Kleinstadtnovelle was fascinating. In one respect predictable — the theme of parochial intolerance is exactly what one might expect from the title — the form is initially startling; a stream of consciousness, modernist experience of a gay teenager’s life, with Brechtian kleinschreibung (appropriate for an author who was one of the last emigrants from West to East Germany).

The other German book was my graphic novel of the month, Der bewegte Mann | Pretty Baby. It’s an absolute hoot! The book is a two-parter, telling the story of a (mostly) hetero guy who gets mixed up with a (mostly) gay group, and König takes every opportunity to take the mickey out of both sides. It was also splendid for my knowledge of (80s gay) German slang.

Possibly the best thing about The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House is the title; not that there’s anything wrong with the book, but it is a fantastic title which perfectly summarises a large part of the message. This is a short collection of texts (mostly speeches) by Lorde, and the oral context allows her great rhetorical opportunities, which she’s happy to take:

There is a difference between painting a back fence and writing a poem, but only one of quantity. And there is, for me, no difference between writing a good poem and moving into sunlight against the body of a woman I love.

Guilt is only another way of avoiding informed action, of buying time out of the pressing need to make clear choices, out of the approaching storm that can feed the earth as well as bend the trees.

There are no new ideas, just new ways of giving those ideas we cherish breath and power in our own living.

The Female Man is of a similar time, and is as explicit in its engagement with 70s feminism, but this time in the context of a sci-fi romp. Russ has great fun with the narrator as a character in the book, and the constant shifts in voice and narrative style create a sometimes bewildering, but highly enjoyable patchwork:

SOMEBODY ASIDES ME IS GONNA RUE THIS HERE PARTICULAR DAY.

‘I know,’ said Jeannine softly and precisely. Or perhaps she said Oh no.

Little did she know that there was, attached to his back, a drowning-machine issued him in his teens along with his pipe and his tweeds and his ambition and his profession and his father’s mannerisms

The Death of Vivek Oji takes place in a very different setting: (small-town?) Nigeria, where a group of young, closeted LGBT people forms around the title character. L G B and T threads all feature in the story, which, set alongside the central investigation of Vivek’s mother, show the importance of not making assumptions.

Shuggie Bain takes place in another now-remote place: the outskirts of Glasgow under the onslaught of Thatcherism. The grimness of the setting and the events is often hard to take, but the central section’s portrayal of Shuggie’s alcoholic mother is very powerful. The social attitudes are also a useful reminder that despite current political horrors, there has been substantial progress in the last few decades.

Night Side of the River does not generally focus on sexuality, though one could draw a parallel with binary distinctions in terms of reality/the paranormal. The paranormal aspect of the stories I had no problem with, but Winterson’s own experiences of the paranormal are interspersed with them, which I found highly irritating (simultaneously credulous and wishy-washy).

The first Portuguese book also fits into the project: Um milhão de finais felizes is the second book I’ve read by Vitor Martins, and it’s very similar to the first. In this case, the protagonist is a teen aspiring-writer with a dysfunctional and homophobic family background. The plot is low jeopardy, mostly just ambling along in the amusing company of him and his friends, which was a pleasant way to spend some time.

The other Portuguese book, Uma menina está perdida no seu século à procura do pai is very enigmatic and suggestive: details are deliberately omitted, and there isn’t any conventional plot development. Once one is aware of that and provided one accepts is, there’s a lot to enjoy here: the protagonists meet interesting characters and discuss philosophical ideas in what I imagine is a higher-class Paolo Coelho-manner.

Finally, a re-read, also from the Lusophone world: I enjoyed Das Geständnis der Löwin much more than I had the first time. Now that I had some idea what was going on, I could see much better the relationships between the characters and different aspects of the plot, and the incorporation of Mozambican cultural ideas (helped also by the discussion which the Portuguese in Translation club held with the author and English translator).

Honourable mention also to two LGBT books I didn’t finish in time: On Earth we are Briefly Gorgeous — Ocean Vuong, and of course Der Zauberberg.

Next month is Black History Month (UK/Ireland edition), which I’ll be celebrating with mostly German (Afro-Deutsch) history and other literature.