London Labour and the London Poor continues, and we’ve just completed volume 2 (just volume 4 to go now).

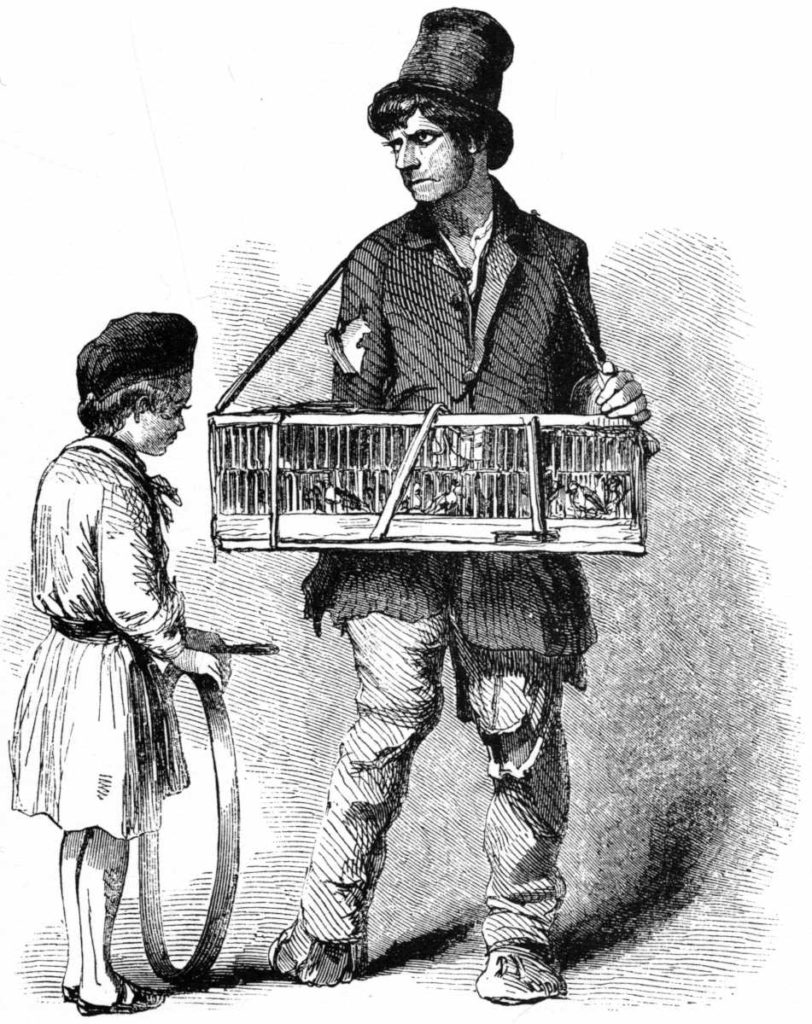

This was rather an enjoyable one, dealing first with street-sellers of an impressive variety of items: stealers and restorers of dogs; bird-duffers, who used various tricks to make ordinary birds look more valuable; sellers of second-hand curtains; and so on.

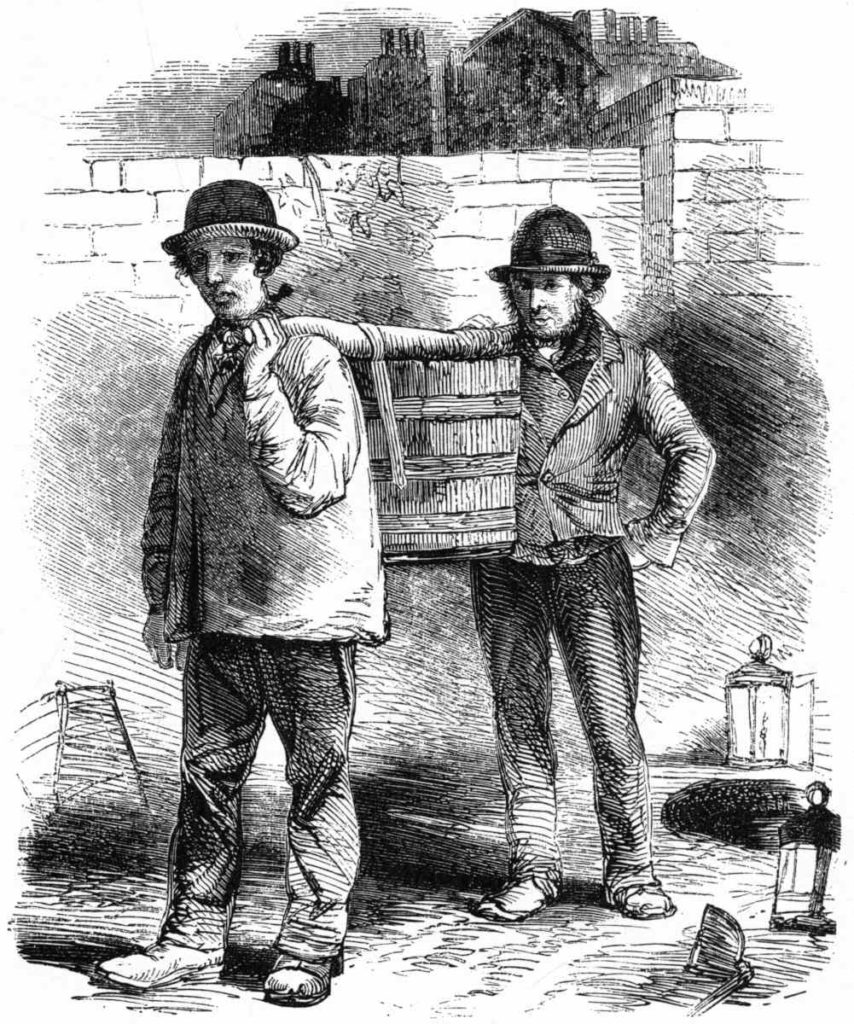

Next came the street buyers and collectors of a similarly diverse range. There were apparently 2-300 full-time collectors of dogs’-dung, mainly for sale to tanners, while others made a living gathering used tea:

An extensive trade, but less extensive, I am informed, than it was a few years ago, is carried on in tea-leaves, or in the leaves of the herb after their having been subjected, in the usual way, to decoction. These leaves are, so to speak, re-manufactured, in spite of great risk and frequent exposure, and in defiance of the law. The 17th Geo. III., c. 29, is positive and stringent on the subject:—

“Every person, whether a dealer in or seller of tea, or not, who shall dye or fabricate any sloe-leaves, liquorice-leaves or the leaves of tea that have been used, or the leaves of the ash, elder or other tree, shrub or plant, in imitation of tea, or who shall mix or colour such leaves with terra Japonica, copperas, sugar, molasses, clay, logwood or other ingredient, or who shall sell or expose to sale, or have in custody, any such adulterations in imitation of tea, shall for every pound forfeit, on conviction, by the oath of one witness, before one justice, 5l.; or, on non-payment, be committed to the House of Correction for not more than twelve or less than six months.”

There’s also a lengthy account of the sewer and night-soil systems. This goes back to the laws of Henry VIII:

“No Goungfermour [night-soil man] shall carry any ordure till after nine of the clock in the Night, under pain of Thirteen Shillings and Four Pence. No man shall cast any urine boles, or ordure boles, into the Streets by Day or Night, afore the Hour of nine in the Night. And also he shall not cast it out, but bring it down and lay it in the Canel, under Pain of Three Shillings and Four Pence. And if he do so cast it upon any Person’s Head,

the Person to have a lawful Recompense, if he have hurt thereby.

By the 19th century, things had become somewhat more civilised:

This night-soil manure was devoted to two purposes—to the manufacture of deodorized and portable manure for exportation (chiefly to our sugar-growing colonies), and to the fertilization of the land around London.

When manufactured into manure it was shipped—in new casks generally, the manure casks of the outward voyage being transformed into the brown sugar casks of the homeward-bound vessels. I was told by a seaman who some years ago sailed to the West Indies, that these manure casks in damp weather gave out an unpleasant odour.

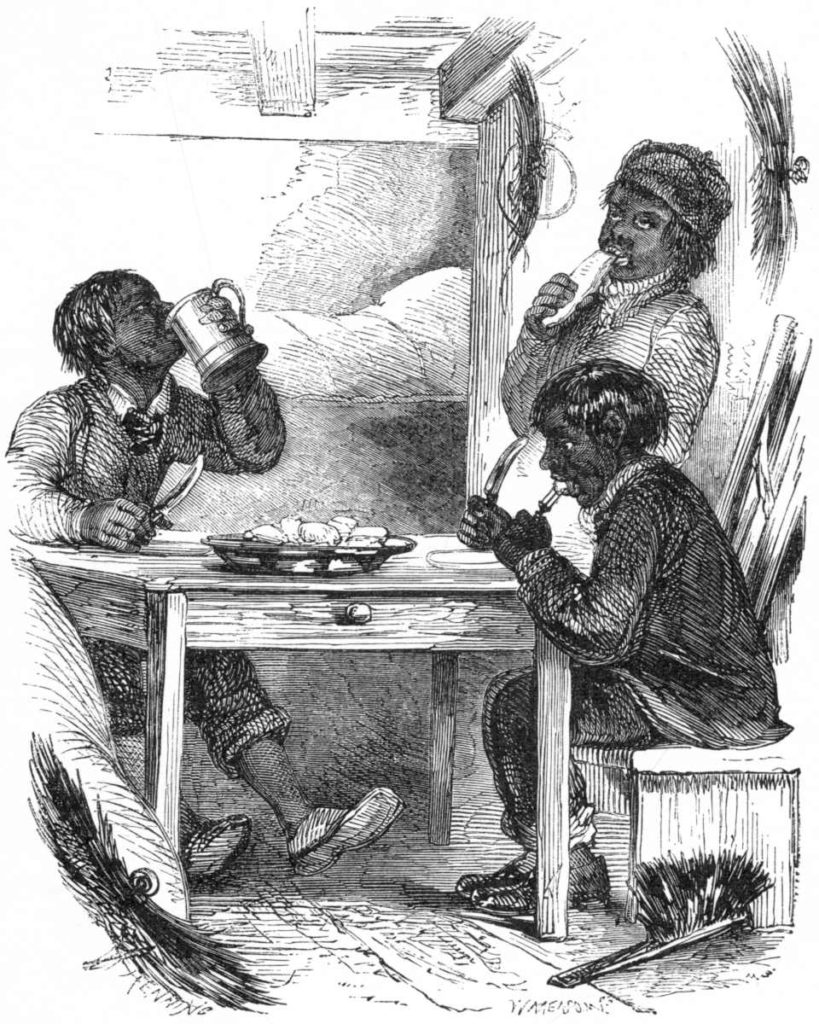

The last main section covers the chimney-sweeps, then just having replaced children with new-fangled machines.

Mechanisation is one area in which the world of London Labour is very recognisable today: there were several trials at the period for new approaches to street cleaning, for example, with cleaning machines which were pulled by horses along the roads, or systems to hose down entire streets with water from fire hydrants, both with consequences for the number of workers required.

Zero hours contracts are also nothing new:

This principle of hiring labourers only for so long as they are wanted, as contradistinguished from the “principle of natural equity,” spoken of by Blackstone, which requires that “the servant shall serve and the master maintain him throughout all the revolutions of the respective seasons, as well when there is work to be done as when there is not,” has been the cause, perhaps, of more casual labour and more pauperism and crime, in this country, than, perhaps, any other of the antecedents before mentioned.

Sounds like a fun read!